“Once more he embarked upon a life of toil, once more he stinted himself in everything, once more he left clean and decent surroundings for a dirty, mean existence.”

-Gogol, trans. D. J. Hogarth

The weekend found Tchitchikov busy at his computer again, perusing his several online subscriptions to local papers; sorting through a few newspapers on the desk in his hotel room; entirely immersed in the endless work of harvesting the votes of the dead.

The checking and cross-checking, that was the difficult part of his work. He spent several hours lining up the names on the obituaries with those on the voter registration lists he “purchased” from both parties. That was the fun part, obtaining these lists from local party volunteers. In truth, hacking into the voting machines was the easiest phase of his plan. Tchitchikov was no computer whiz, certainly not, but he was nonetheless resourceful. He’d paid a local community college student of healthy pridefulness and questionable morality to do this part. She had spent not quite three hours of honest work.

Plug in the names to the master list of voters, plug in their votes to her simple interface, and voila! The dead are among us again. Thankfully, unlike George A. Romero’s depiction, they only show up for the one day, though just as frightening these undead are politically minded. Selifan, less politically minded, had gone his way to work a tan into his pale, Russian immigrant skin. This Saturday, Tchitchikov was interrupted by a call from a Florida fellow.

“Hello?”

“Is this Paul Tchitchikov?” The receiver spoke with a nasal voice.

“Yes, this is he.”

The nasal voice continued; Tchitchikov imagined a pinched nose. “The Paul Tchitchikov formerly of Saint Petersburg? And currently of Liberty, Tennessee?”

“Saint Petersburg is currently the name, as we have not had a war recently, and yes, this is that Tchitchikov. How do you know of Liberty? Wait—who is this?”

“Thank you.” And the phone hung up.

A dark pit grew in his stomach. Tchitchikov was not fond of surprises, let alone foreboding ones, and to him, unlike Selifan, un-knowledge was the greatest discomfort of all. He had many enemies—this must be, for all good men have a great deal of enemies—though his had the dubious distinction of being unknown to our hero. This might produce thoughts on Tchitchikov’s character and the nature of his dealings, but I would like to quell those thoughts now. Perhaps a piece of backstory is in order.

Pavel Ivanovitch Tchitchikov, known to us as Paul Ivan, was born outside of St. Petersburg, Russia. Should one trace back his life’s travels to find his birth certificate, one would come across two difficulties: many of the smaller towns outside of St. Petersburg had suffered fires in their civic records departments around twenty years ago, should one discover from Tchitchikov the exact town of his residence; the second being Tchitchikov’s own reluctance to name the specific town of his childhood, though we should not be one to impose upon a man for personal information he does not wish to give freely. He has his reasons. But I trust his word upon his age—thirty-five—and in addition, his immigration papers are dated likewise from twenty years ago, marking St. Petersburg as his previous city of residence, so he, then, arrived in our country as a teenager. It appears he didn’t bring his parents along, and that pain is perhaps one reason for him to keep these cards close to his chest, as the saying goes. He does keep many dear things to his chest, many secrets and hopes and dreams.

Selifan, too, immigrated from Russia incidentally, though Tchitchikov never inquired when or from where, or at least he never said he was knowledgeable of those particulars. Selifan’s age is but a couple years more than Tchitchikov’s, and the closeness in age and closeness in situation brought about a closeness in hearts: Selifan was one of the few, or perhaps the only one, whom Tchitchikov could confide in. Of Selifan’s employment, I know not too much, other than a few brief food-delivery stints and the such; though of Tchitchikov, records state that he worked for the government in a small way, as a postal clerk in Virginia. He moved to Liberty, Tennessee and worked at the post office nearby for the greater part of his career; Selifan’s movements, as due to the nature of his employment, are unfortunately more dispersed. If the postman Tchitchikov had inclinations toward deeper government work, there were no outward signs of it nor would his immigration status allow it. What did he do in Liberty, Tennessee? Even I cannot say exactly. He could have walked the main thoroughfare, which was certainly walkable, and shopped at the local market, a one-and-a-half room building that offered tools and paper goods and unperishable foods. Perhaps he did not do much. But thus far we have seen a mind like Tchitchikov’s is always at work, even at rest, or rather, especially at rest, so our presupposition of his settling into a restful little town in the middle of Tennessee would be marred if we supposed he would likewise be restful. To sum up, the assumption that Tchitchikov were a personage to acquire very many enemies over the course of his lifetime were to ignore the rather mundane nature of the course of his lifetime. The phone call was indeed puzzling.

The triad of a sudden call from a Florida number inquiring about him, and not answering who was inquiring, and furthermore, mentioning the small, unknown villa of Liberty, Tennessee, produced a chill in his heart. Perhaps I should speed course, he thought. Mayhap I have said too much to a congressman.

Selifan entered the hotel room at this moment.

“It was not you who had called me,” Tchitchikov asked, “just now?”

“What do you mean?”

“You didn’t place a call, correct?”

Selifan was perplexed. “Your phone would have registered my information, would it have not?”

“Then from a payphone?”

Selifan shook his head. “A payphone? I have not seen one of those since—God unknowing—I cannot recall since when. Why do you ask? Did someone call?”

Tchitchikov’s tongue touched the tip of his lip in thought. He withdrew it again. “No, it must be a scammer.”

“We are in Florida, the Land of the Scam.” Selifan laughed. “I read that on a license plate, I assure you.”

“Yes,” Tchitchikov said. His mind processed other trajectories. “That is likely so.”

“Here.” Selifan offered a meal: fresh calamari and many fries and much ketchup. “Since you are hard at work. I tried their fish this time. It was palatable. And the fries you loaned me yesterday are repaid.”

Tchitchikov thanked his companion for the generous heaping of food. “I see you are deep in thoughtful work,” Selifan said. “I shall be on my way again.”

“Wait,” Tchitchikov said. “You are a lobster.”

“You wanted something other than squid? Unless I heard correctly the first time, in which case you are senseless again.”

“No, Selifan, you are red as a lobster.”

Selifan blinked his eyes. “The expression, here, is red as a beet.”

“Maybe so, but I hate beets. They have too strong a taste of soil for my tongue.” Tchitchikov pointed to the bathroom. “Go check.”

Selifan did check and came back smiling. “Excellent!”

“Excellent?”

“Yes,” Selifan said. “I have the tough start of a healthy, American tan.”

“You have the tough start of a healthy, American cancer.”

“Death is always the risk of beauty,” Selifan said.

“Does it not hurt?”

“It shall,” he replied, “and that is how I know I have accomplished something for myself. No pain, no gain.”

Tchitchikov cocked his head. “Yes, I suppose this makes sense after all.”

“What makes sense?”

“Never mind. You go and develop the next stage of cancer on your tan.” Tchitchikov returned to his laptop. “The food looks delectable. Fried calamari is … is … I am thinking of a type of delicious food, but am short on words.”

“It is addictive like Cheesy Cheetahs?”

Tchitchikov recoiled internally. “I suppose, to some. I don’t know if I could claim calamari to be the Cheesy Cheetahs of the sea. But I believe a first bite of this will determine that. Regardless, thank you again for the food.”

Selifan returned to his seaside bronzing, leaving Tchitchikov to toil through the night.

****

Sunday was sleep-in day.

It was unusual for Selifan to be up so early, before eleven, on a Sunday morning. Moreover, it was very unusual that he would be watching the television, and trebly so that the news was on the same television.

Tchitchikov turned over. “What is this…?”

“I overdid it,” Selifan said. “I couldn’t sleep.”

Tchitchikov rubbed his eyes. “And now I can’t. Misery needs company, and some company needs misery.”

“I am aloed more than the blasted plant itself.” Tchitchikov focused his eyes upon a shiny Selifan. “I feel I have spent our last savings on this expense.”

“Is this true?”

Selifan stared. “No. That was a joke. But I appreciate the concern.”

Tchitchikov lay back down. “How are you doing, then?”

“Fantastic.”

“Fantastic?”

Selifan nodded. “This shall become the most fantastic tan I have ever had.”

Tchitchikov grumbled. “Could you at least turn the television down?”

“I need the extra volume to deafen the burning sensation.”

“Then what is this?” Tchitchikov bent upward again in bed. “Why the news?”

“I need the extra news to deafen the burning as well. I have discovered the affairs of our world rather effective in drowning out other lesser pains.” Selifan turned back to the tube. “You have struck in me an interest for it.”

“It seems an appropriate show for a masochist.” A light switched on in him. “Let me see it. Is there mention of any local charlatans?”

“Yes,” Selifan said. “You must see this one.”

Tchitchikov’s heart pounded, That was fast, he thought. But on the screen was a young woman of short, pinked hair and a studded ear.

“…to recognize our pain, our suffering,” Jenna said. “And they d%*# well have to do something about it!”

The camera shifted to Andy and his white denim jacket. There was a new patch this time. “We’re asking the Governor to fix the massive problems with the HealthChoices website, and to expand health insurance coverage. People are dying and going bankrupt every day. And secondly—”

Jenna interjected. “Crush us, and our bones will stab your feet! Long live the political revolution!” Andy was stunned by her shrill voice. “Tell Governor A$*#*^% that.”

The television returned to the newscaster. Selifan stood up and paced back and forth stiffly. “It’ll be a lovely one,” he said to himself.

****

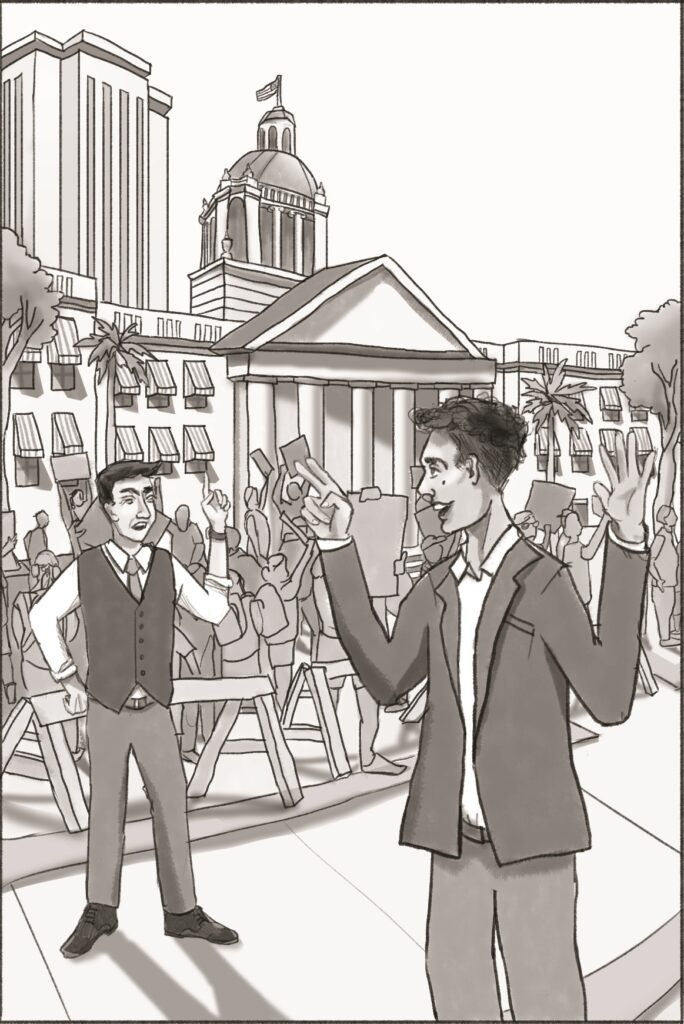

Tchitchikov was not certain why he was drawn to the protest at the State House; there, he would not meet anyone of political import, nor would he further the designs he was working upon. Still, he followed the mysterious pull and furthermore, Selifan was strangely agreeable to the two-hour drive, made quicker by his state of comfortable discomfort.

“I am glad you agreed to this trip,” Tchitchikov said. “I wasn’t sure it was a reasonable request.”

Selifan’s head was into the wind, practically out of the window. “I don’t mind the drive,” he said. “The breeze is helpful.”

Tchitchikov was more than normally curious about his travel-mate, but allayed his curiosity for the time being. He had other thoughts on his mind, namely, whether Jenna and Andy would still be there, or if they would have been dispersed by police by the time they arrived.

Thankfully, this fear was unfounded. Rather than dispersed, the crowd had enlarged itself: signs, chants, shouting, effigies as well. It was difficult to spot anyone, let alone Jenna and Andy in the crowd.

“Selifan, do you see anywhere that young woman on the—” Tchitchikov turned around to face a shirtless muscled stranger. “Blast, where did that lobster scuttle to…?”

Tchitchikov waded through the vocal crowd. If Fairwell’s fundraiser was a simmering pot of agitation, then the protest was that plus onions, teary-eyed from despondency; meat seared on the flames of anger; and several potatoes of discontent. The malcontents had much reason to boil over, for the malfeasance of the state government had stirred the pot of—I am not sure at this point what I have made—justice, maybe. Tchitchikov tired of his search, and exited the crowd so as to sit and stew—this is what I have made, a savory pun!—on a sidewalk opposite the State House.

From a distance, the crowd writhed like one multi-legged animal, heaving as in the throes of either death or birth. Tchitchikov watched, entranced by all the passion out there, hoping to speak their truth to the powers that are. He was interrupted from his reverie by a young man. “Do you have a smoke?” he asked.

Tchitchikov sighed. “Do I look like a smoke-embalmed mummy? Does my breath smell like stifled embers? Everyone asks. No one thinks.”

The young man laughed.

“What is funny here?”

“You, I suppose.”

“Come now, you rascal—” “No, wait!” The young man held his hands up. “You got me!” He laughed further.

Tchitchikov pondered the various options of engagement that lay before him. He sized him up: the young man was cleanly dressed, and sharply, with dress pants—though cheap—and a dark jacket over a pale shirt—also cheap, some bare threads at the elbows. The young man was cleanly shaved, apparently very cleanly, and recently too, that spoke to the care he took in quality toiletries. Most importantly, he wore a large, but slightly devilish, grin. The whole presentation before Tchitchikov was effective for its purpose. And what purpose was that? To remind Tchitchikov of a young doppelganger of himself, he was certain.

After a few moments he decided not to box him after all.

“And who might you be, youth-of-protest?”

“I might be Aris,” he said, “And who might you be, lacking-of-smokes?”

“I do not smoke. That might be a surprise to a young dolt such as you.”

“Well, well. At least you didn’t punch me. You almost looked like it.”

“Yes, that is true.” Tchitchikov’s interest was piqued. “How could you tell?”

Aris looked him up and down. “You started doing this thing with your hands.” He motioned with his fingers, wrapping them around in the air quickly, trying different angles and positions until landing upon one: he gave Tchitchikov the bird. “I’ve learned to recognize I might get punched when people do that.”

Tchitchikov smiled. “You have a head on your shoulders. Then what are you doing here?”

“I have a few friends here. I came to the party.” Aris shrugged.

“Now you are a young fellow—”

“That being a term relative to my elder.”

“…yes, but perhaps you can produce someone for me. She and her boyfriend are in this crowd, though I don’t know how much they’d distinguish themselves from everyone else. In any case, she has short, pink hair, a rose tattoo on her shoulder—”

“Jenna?” Aris scratched his head. “Sure, I’ll go grab her.”

“You know her?” he asked. But Aris had already walked away in some specific direction. Soon, he was swallowed into the protest.

Tchitchikov tapped his foot. He watched the crowd slowly shrink and could sense they would dissipate in a couple more hours. After fifteen minutes, Tchitchikov stood up and turned to leave.

“Hey, wait, YOU! Guy, you!” Aris jogged over and panted before him. “Maybe … I should … stop smoking…?”

Tchitchikov was at the ready for a reply when he heard Jenna’s voice and saw she and Andy sift out of the crowd. “Ohemgee! ‘Funny Russian nut’—I KNEW it! Ten bucks, Andy!” She slapped his back.

“Paul Ivan, how goes it?” Andy and he shook hands. “I take it you know Aris?”

“I do now.”

“He … does…” Aris huffed.

“How did you know we were here?” Jenna asked, “Ohemgee, did you see us on TV?”

“I did.”

Jenna gasped. “I’m famous!”

Andy laughed with her.

Aris recovered some of his breath. “You really do … know everyone.”

Andy nodded. “We know all the crazy Russians worth knowing in these here parts.”

Jenna tugged at Tchitchikov’s arm. “You should come! We’re going to try my new slogan! I want to see if it’ll catch on!”

Jenna continued, “Governor come out and meet. Do not crush us with your feet. If you do we’ll stab you back. And if you can’t we’ll still attack.

“Do you like it?”

“That’s clever,” Andy said.

Tchitchikov nodded. “It’s not too bad.”

“Yes, it took me a while to come up with it,” Jenna said. “Come on, let’s practice!”

Tchitchikov shook his head. “I’m not one for such things.”

“Okaaaaaay,” she said. “But come by the office.”

“Which office?”

“Fairwell’s, dummy.” She pushed a political card into his hand. “We’re organizers for him. We’ll set you up.”

“I might consider,” Tchitchikov replied.

“You’d better consider,” Jenna said. “Let’s go, Andy, before Fairwell speaks. Aris, come on, you too!” She winked at Tchitchikov. “I always wanted to save the world.”

The three of them reentered the protest. Tchitchikov sighed at their youth and energy.

****

Tchitchikov and Selifan rejoined at the same sidewalk. As it was late, the sun came down on their ride back. Tchitchikov watched it go down in the side mirror. Selifan missed the sun, too.

As the two retired to their hotel room, Selifan reapplied another bottle of aloe vera, and Tchitchikov rechecked his email and messages. There was a text from the same number that had called him earlier that day. Tchitchikov’s stomach plummeted, a combination of unknowing and, now, knowing; not knowing what to happen, but knowing by whom. He placed the cell phone on the nightstand and did his best to sleep.

The text had said: You have been found, “Fyodor.”