“Tchitchikov reflected that he had indeed fallen into an aristocratic wilderness.”

-Gogol, trans. D. J. Hogarth

Fyodor Nosdihanov was the progeny of two authors, one very famous, and one incredibly obscure: the aforementioned Fyodor Dostoevsky, and the never-mentioned Denis Nosdihanov. The former was, of course, known for his deep psychology and philosophy, and of the latter, he was unknown for a picaresque character in poorly structured plots. Their child, so to speak, was not dissimilar to Tchitchikov, for he and he were of the same body. The difference, then, was in appearance: Nosdihanov appeared to have acquired voter registration lists from both parties, being neither registered in either party, nor registered as a physical being by the government, and also purchasing these lists from one party for the excellent price of a few alcoholic drinks, and also to have wooed a married woman with them to do so; and Tchitchikov appeared to have not. These are the particulars and sum of their differences.

Tchitchikov did not sleep a wink the night through. That night he discovered Selifan mumbled to himself at approximately the middle of the night, senseless things that made it seem he was awake, though speaking another language. He may have been speaking of unceasing power in this language, or the comfort of a warm, berried pancake. Tchitchikov was unsure. At first Tchitchikov answered him back, and Selifan agreed, though in his own bumbling language; at which point Tchitchikov realized he was speaking perfectly fluent Nonsense. This Monday, Tchitchikov felt Selifan had muttered the solution to this proverbial monkey wrench in the works, though he had simply not been able to understand it.

Tchitchikov heard noises of Selifan in the shower.

He got up out of bed and paced about the room, unable to accept that Selifan beat him and delayed his morning routine. Tchitchikov looked at the clock, and noted that it was late, very late for a weekday: it was nearly eleven o’clock. Fear and exhaustion heaped themselves upon his mood in equal amounts, then stirred him about on his feet at a faster pace.

“Oh, you are awake?”

Selifan exited with a towel wrapped around himself, and with a most vicious tan intruding upon most of his skin. “I was asleep?” Tchitchikov asked.

“You snored loudly, I suppose, for about an hour just now.”

“I didn’t realize.”

“Come on,” Selifan said. “Hurry up. We have much work ahead of us.”

****

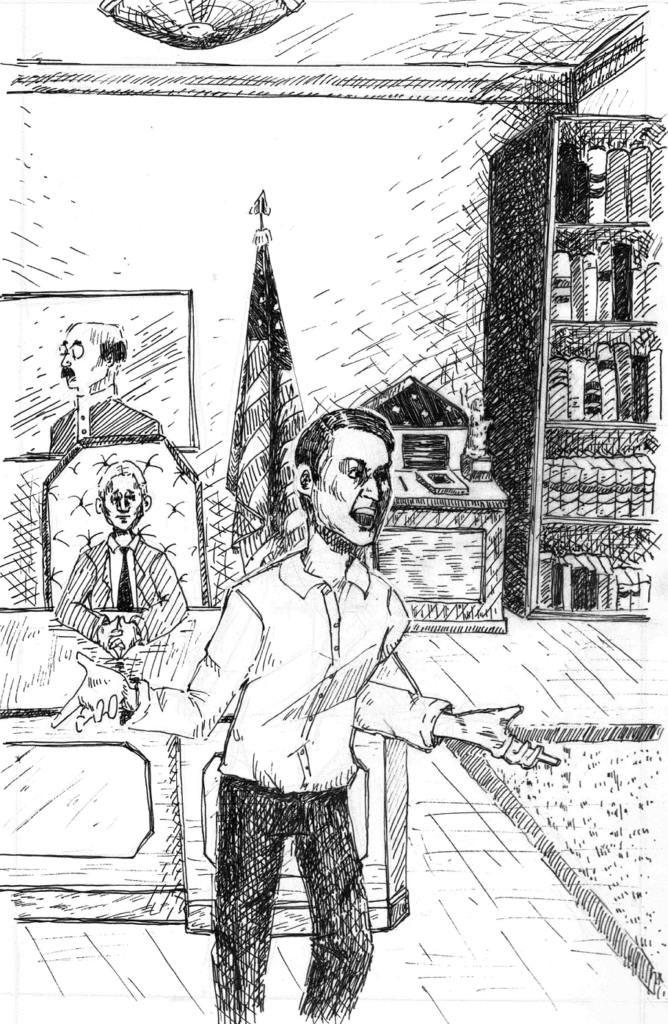

Their first stop of Monday was to Representative Stoddard’s office. Stoddard was, or rather would be in any other context, a wholly incapable man. He was not gifted with self-composure nor beauteous speech, and it was said during his school upbringing, by one certain middle school teacher R—, that he could not compose a sentence with all three of grammar, main focus, and unique thought. That said, he was a gifted politician. His campaign drew in a fair amount of local talent, attributable either to a mystical je ne sais quoi or some cosmic accident. One could think the local political talent saw a blank canvass, and wanted graciously to fill it in. As to that important canvass of the countenance, I cannot say much beyond his pale flesh and the neat, blondish parting on top; but of his hands, I can certainly say that they drew Tchitchikov’s attention. They frittered constantly, knitting more deftly than Arachne. As a politician, he would hide behind a podium, bend into a type-written speech, and offer it to the mostly uninterested media before him, dodging exposure of this weakness. In front of Tchitchikov, or any voter for that matter, it became apparent that Stoddard was not born for conversation nor grand speech nor independent thought; but rather, he was made for it. He was a rising star in the state party, and, as such, was blessedly able to avoid most any constituent. He was an enviable politician by most accounts.

“I am not sure what you are trying to say, Mr. Chee-chee-koft.”

“Tchitchikov. Not ‘coughed.’ But this is a minor matter; the name is a Cossack one, and of little consequence, much as a sneeze in a windstorm. What is of great consequence is why I shan’t have the delight of pursuing private conversation with Representative Stoddard, Mr. Raymond.”

Stoddard had an advisor nearby him most nearly all the time. The advisor was a Mr. Stu Raymond, a high school friend with whom Stoddard had become acquainted on opposite ends of a chummy high school hazing. Stu maintained certain characteristics from his high school career, namely assertiveness, an interest in sports, and a penchant for wooing women. It was these personable characteristics that would have benefited Stoddard’s political career had he possessed them, though vicariously through Stu did his career enjoy these benefits. On occasion Stoddard and Stu would reflect upon their separate, yet intertwined experiences through those formative years of joyful juvenile delinquency, often upon Stu’s request and with his laughter and often with Stoddard’s quiet contemplation. “He does speak, does he not?” Tchitchikov asked Stu.

“He does. Show him, Alfred.”

“I do,” said Stoddard.

“Now,” Stu said, “what is it you’re trying to say again?”

“I understand,” Tchitchikov said, and truly meant it. “I am merely saying it should be helpful to consider reaching out to our rather lively—ahem—congregation. I believe you would find the time spent to be most profitable, Stu. Both of you.”

“So,” Stu stood up and paced around his chair. “Allow me to understand what you mean: we reach out to your congregation, and we gain their votes.”

“Yes, that is all I’m trying to—”

“A little donation, to some handful of votes. It would be a slam dunk,” Stu motioned a distant shot with his hands. “Done, finito. Easy peasy.”

“Why, yes! You do—”

“Then, my question is how many votes—right?—are in a handful, and how many resources are required? That’s the calculation, right?”

Tchitchikov nodded. “It would be most profitable to you, I assure—”

“Wait, because we must consider,” Stu pointed a finger in the air, balancing an invisible ball, “this: should our team be caught in any scandal, this little cheat would ruin us, cause us to lose the entire championship, if I may put it that way. We would have lost all because of some unknown handful of points—votes.”

Tchitchikov furrowed his brow. “Well, not an unknown number, but…”

“You see,” Stu said, “when you say this would be profitable to us, you really mean potentially dangerous. Really, it is profitable to one person here.” Stu pointed his ball-finger. “By which I mean, of course, you.”

“There are benefits to both parties.”

“I don’t see them,” Stu said. “I see a joker trying to make off with my money—I mean, our money. Our time, too.”

Tchitchikov attempted to parry. “I do not mean to spend overly of your time, and furthermore—”

“Then you only want to waste my money. That’s the calculus in front of us. That’s what I see.” Stu felt the word “calculus” was extra weighty because he had never made a passing grade in it. “I think we are done here.”

In a normal frame of mind, Tchitchikov would have dealt reasonably with Stu and left the contest between them only a few points behind, so to speak. But Stu’s personality had aggravated him, and against his better judgment, Tchitchikov decided to call a new line of play. “Yes, I see what you are saying. It is a risk, and perhaps things should never be risked, lest the whole project—the whole exercise—come tumbling down. You make a fair point,” he said to Stu. He passed the conversation to Stoddard, “I would not want to risk your neck. It is unfair of me to presuppose a thing.”

Stoddard fumbled. “Why, I…”

Tchitchikov returned to Stu, “I suppose I should be more cautious. I am unlearned of your situation, and I apologize for my offense. Consider it the offense of a hapless fool.” To Stoddard, “Yes, a hapless fool. Besides, such a decision should not be left in the hands of a doddering imbecile, yes? It could be a great risk.”

“No, I suppose not…”

Stu reddened. “What is it you’re trying to say? Are you a man? Or are you only words?”

Tchitchikov smiled to Stu. “I have words, yes, and many of them.” He turned to Stoddard. “Some of us are so blessed.” Tchitchikov addressed Stu again, “But I consider myself a man of many words, my actions my failings, my strengths my mind and inner resources. I apologize for this, for myself. I imagine you ask for many apologies of people, for who they are.”

“What do you mean?” Stu said.

“I mean,” Tchitchikov glanced sideways at Stoddard. He was following his words intently. Tchitchikov answered Stu, “I mean to say that you may ask of me an apology for my impertinence, my intelligence. But there will be a time, perhaps soon, where you may no longer ask that of me.” Tchitchikov continued softer with Stu. “But perhaps I am misled, though I believe in my heart intelligence is a difficult thing to crush down, as its voice echoes in our minds well after it falls from our ears. But crush as you might.”

“You’re making no sense,” Stu said.

“Stu,” Stoddard said, “there seems some sense here.”

“And I agree,” Tchitchikov adjusted to a normal loudness. “And should you, too, dear Stu. You may give us a few words, or likely, a grunt of affirmation—that means you agree.”

Stu growled. “You are an ignorant buffoon you—”

Tchitchikov grinned. “Not a grunt, but close enough to conform to my request.” Tchitchikov stood up. “I shall be going, with but one last word: do not crush the weak beneath you. Their bones will stab your foot-soles if you succeed. And if you do not, their hands shall drag your shins into their gaping mouths.” Tchitchikov’s stare was venom. “Take it as you like, but I intend it a parting shot—not a sporting phrase, but rather consider this my end and your warning. It comes from Parthians who—well I trust you know someone who can explain ancient history to you.”

Stu fumed, nearly shaking. “You’re a real piece of shit, Paul. Pardon my French. Arrogant assholes always get what they deserve.”

“We do,” Tchitchikov said. He nodded to Stoddard on his way out. “Representative.”

“Wait,” the representative said.

“Yes?” Tchitchikov replied.

“Never mind,” Stoddard said. “Stuart and I have some discussions to make. Thank you for your time.”

“Thank him? That ignorant jackass?” Stu shook his head as a duck might shake rainwater from its rear parts. “Alfred, have you lost it?”

“Give me a moment with him,” Stoddard told Tchitchikov. “Now is an inopportune time for us.”

“It seems it has been for some time,” Tchitchikov said. “But I shall see myself out. Good luck.”

Stoddard’s hands relaxed. “Good luck.”

Tchitchikov’s Hail Mary, then, looked to have been caught.

****

“He is not one to use our list.”

Selifan frowned. “Another Fairwell?”

“In a way, yes,” Tchitchikov said.

“Another waste of time.”

Tchitchikov mused to himself. “Not so, but no financial gain.”

“What other gain could we seek?”

Tchitchikov shook his head. “Never mind. There is one thing left, my meeting with Taber, but that is long from now. I believe we have some respite for some time.”

“Do we?” Selifan asked.

Tchitchikov sighed to himself. His day-dreams of late had been shifting in forms, and he entertained these new shifts more than he’d ever had in his life. “Hmmm?”

“There is one more person we should attempt today.”

“And who might that be?”

Selifan smiled. “Kingston.”

Tchitchikov stared out the window. “Why? He has no power.”

“He has money.”

“He does.”

“And it is said he shall receive power soon.”

“Maybe.”

“And a newly minted politician is especially moldable.”

Tchitchikov found his logic sound. But he surprised himself. “Perhaps another time. I am not in the right mood.”

“Right mood?”

“Yes, mood.”

Selifan glinted. “Does that matter now?”

“Perhaps.”

“Perhaps you forget,” Selifan said, “that we are in this business together, in equal shares. That it is my risk with yours, and my reward as well. Kingston seems a low piece of fruit to pluck, does he not? Unless I am mistaken.”

“No, you are not.”

“I’m glad to hear it.” Selifan started his car to more cranky sounds. “Let us go.”

****

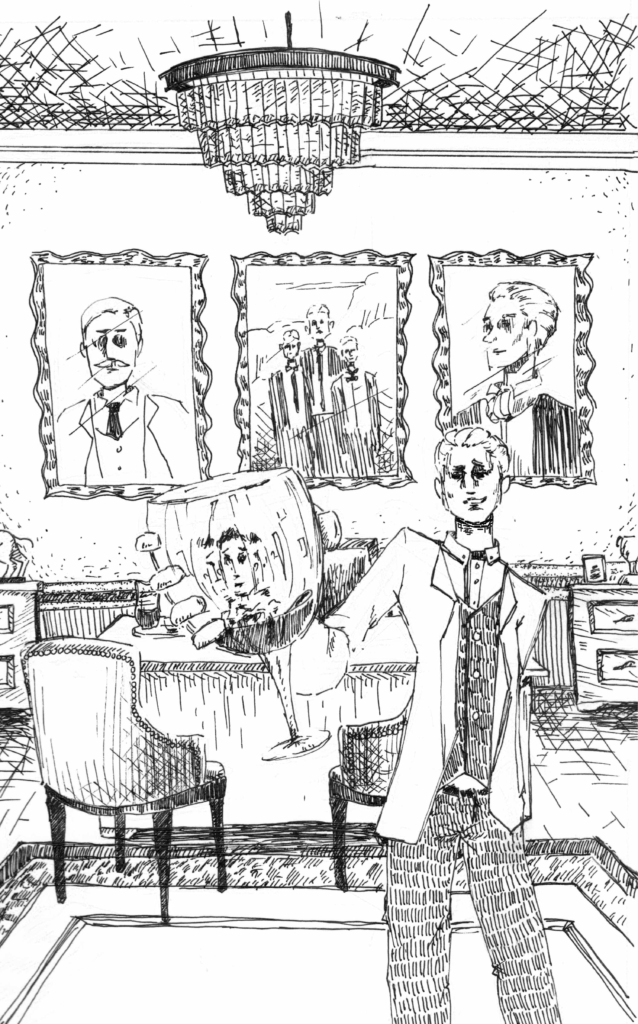

Selifan was accurate in his assessment of the challenger Kingston. The Kingston family was one of the last great political clans in our country. James’ lineage was formidable and impeccable, that is, what minor blemishes on the name that had been there were graciously forgiven and forgotten by colleagues and constituents alike.

Like all Kingstons, James’ face was handsome: chiseled features, a wave of blonde hair, boyish smile. He was very nearly a living ghost of his great-uncle, their faces coincided that much. In fact, most of the male lineage were instantly recognizable as one of the Kingston clan, that particular brand of human being who was more than well-liked, but well-adored; whose family took their summer vacations on Martha’s Vineyard, away from inquisitive eyes; who found political success wherever and whenever they showed. James’ biggest asset, other than a youthful version of his family’s face, was his and his family’s legendary sense of speech. His great uncle had had this gift, had risen the political ranks propitiously, and he had ruled his particular dominion generously and graciously. James, rather far removed, had yet some semblance of this greatness, which, with even a dash of it, beckoned toward unbridled success. His speeches were enlightening. It left the listener elevated, transcendent, hitting appropriate notes of unexpected rhetoric and emotion, such that after the speech concluded, one was in such a daze as to not recall the matter of the speech. Such was the power and draw of the Kingstons, of James included, that they were often married at youthful ages by lucky models of women, and their youthful temperaments were tempered by the desire to nest and produce more; at least, the wives never complained otherwise of their temperaments.

Tchitchikov felt both intimidated and fortunate to have a meeting with the man. His vest and shirt felt warmer than usual, despite the powerful air conditioning of James Kingston’s office. To make matters worse, Kingston was minutely busy, and left our kindly hero to simmer in his office, alone, and wonder what future might befall him should he come into Kingston’s good graces. He looked around: a few casual pictures of him with the Mahatma; with retired world leaders; with other, more famous—as of yet—family members. By the time James arrived, Tchitchikov was surfeit with dreams of overwhelming grandeur.

The door opened.

“Why hello,” Kingston said. “I’m glad to meet you, Mr. Tchitchikov.”

“As well as you, myself,” Tchitchikov felt his firm, personable handshake. “I am glad you could make the time.”

“I’m always happy to make the time for a future constituent!” Kingston smiled that Kingston smile. “Tell me, what’s on your mind?”

“Well, Mr. Kingston—”

“James, please.”

“Mr. James, I wanted to preface my offer of assistance with noting that you are in a tight race with the incumbent, Fairwell,”

Kingston laughed. “Why yes, thank you! That’s not a tough thing to note, my friend.”

“Then perhaps I should speak of the assistance I might have to offer.”

“Nonsense,” he said. “Take a seat, first. How do you take your coffee?”

Tchitchikov had a better sense about this cup of coffee than Fairwell’s. “Let’s try two creams, one sugar.”

“You’re not sure how you take your coffee?” He smiled.

“No, that is—that is not to say I don’t know, but I don’t usually drink it.”

He opened a beverage fridge. “Let’s see, we also have some water, some ginger ale, and a few more drinks of varying strengths.”

“Varying strengths?”

Kingston pulled out a bottle of white wine. “Unless you prefer a liqueur.”

“I’ll have the wine.”

“Good choice, good choice,” Kingston produced a corkscrew from his pocket. “Here we are,” he poured into two glasses, also seemingly from nowhere. He offered one. “For you.”

The chill of the wine fogged the wine glass. “Thank you.”

“Cheers,” he said. The two glasses clinked. “Now, what are you doing in Jacksonville?”

The white wine was not of the quality Selifan and Tchitchikov would usually share. “I didn’t think I was such an esteemed guest.”

“Why not?”

“We have just met, have we not?”

“We have just met!” Kingston took a healthy sipful. “And you’re the clever kind to notice my generosity. Yes, we have not met before, but I know a little about you.”

“You do…?”

“I do,” he said. “Let’s say the town is a-tittering with tales of the legendary Tchitchikov. You’re the one with the bodies in your car, right?”

Tchitchikov shifted in his seat. “I don’t believe I should answer that.”

“Not real bodies, but more impactful. And I believe you shouldn’t answer that, either. The question to me,” Kingston slumped down in a large leather chair, “is not what you ask of me, but how you respond to what I ask of you.”

“But what do you mean?”

“I mean: I don’t want those votes.” Kingston leaned in further. “I don’t give a damn about votes. I want something far more precious than some tick marks on a piece of paper: I want dirt.”

“Dirt?”

Kingston leaned back again. “You know, dirt. Not the kind you’d bury your bodies with, the kind you bury your opponents with.” He smiled. “That kind.”

“I do know of what you mean, but I do not possess any.”

“Then you should.”

Tchitchikov felt warm under his shirt’s collar. “Why?” He regretted asking mid-utterance.

“Because,” he said, “you’re one in a wee bit of trouble, as they might say. And green cards don’t exactly grow on trees.” Kingston stood up. “So tell me, what dirt have you heard about?”

Tchitchikov shook his head. “I told you: none.”

“You were at the protest,” Kingston said.

“And what ‘dirt’ might I uncover at a protest?”

“That’s not the question here.” Kingston retrieved another glass of wine for himself. “The question is ‘when’s the next one?’”

“What do you mean to say?”

“What I mean to say, Mr. dear Tchitchikov, Paul Ivan Tchitchikov—that has a lovely ring to it! A name, that’s the first start of a politician, a real, true politician—what I mean to say Mr. Tchitchikov, is that you should get to know when the next protest is. You should get to learn a lot more than that about Fairwell. And you should come back only, and only if you have something that the media might want to hear about.”

Kingston’s kingly smile again. Tchitchikov’s stomach roiled.

“Come here. Certainly you take your vodka straight, right?”

“I believe I am done,” Tchitchikov said. “I should leave.”

“Paul,” Kingston paused Tchitchikov in his tracks. “Remember what I said. You are a boy in deep trouble.” He lifted his glass. “Cheers.”

****

Tchitchikov sat numbly in Selifan’s car.

“And how was it?” Selifan asked.

Tchitchikov mumbled.

“What? I cannot hear you, dear friend.”

Tchitchikov shook his head and stopped. “Selifan.”

“Yes.”

“I believe we should stop course. I do not feel comfortable with our pursuits.”

Selifan’s eagerness melted. “Tchitchikov, what do you mean?”

“I mean we head home to Tennessee. I mean we leave Jacksonville now.”

Selifan shook his head. “Why? But we have Taber to speak to tonight!”

“Selifan, let me not say exactly why.”

“I believe you should.”

Tchitchikov looked at his travel companion. He could not muster the words. “The interest has been sapped from me. That is all I can produce now.”

“That is all?”

“That is all.”

Selifan shook his head. “That is not good enough.”

“But, Selifan—”

“No, no more ‘but Selifan.’ Selifan has been plenty a butt to your jokes.” He turned his eyes to Tchitchikov: more poison than a cobra. “I know what you think of me.”

“Selifan, do you really—?”

“No,” he said. “It is time your speech ended, and mine began. It will—no, it must, it must begin on this point: Why is Tchitchikov allowed to guide the both of us? For the past four months, it has been you who has determined to where I drive.”

“Selifan…”

“Do not ‘Selifan’ me, you buffoon of a madman!” He nearly coughed in anger. “We have made one sale, with only a handful of days to an election, and here you are: ‘I no longer wish to.’ Well, then, my car does not wish to, either.”

“Dear Selifan, I am sorry but—”

“Keep your sorries and your empty words. And do not ‘dear Selifan’ me anymore, Tchitchikov. Is anyone so dear to you as yourself? That is what I think every time you utter the damned phrase.”

Tchitchikov was mired in a thick tarred bog; he lost his strength and the will to move from it. He saw it creep slowly up past his waist, up at his chest. “Selifan, I am sorry that I have so abused you.”

“Twice now, that word sorry! I am sorry that you shall no longer abuse me,” he said. “Goodbye, you Russian idiot. Out.”

“But we have split the room tonight,” Tchitchikov said.

“Keep it,” Selifan said. “I’m heading anywhere but.”

“Selifan…”

Selifan got out of the car and opened Tchitchikov’s door. “Now.”

The tar was above Tchitchikov’s lips, and he could only nod.

The car shuddered into movement, and soon was gone.

Tchitchikov reassessed his plans, all of them. Like so many china dishes on the ground, a masterful bull laid his plans at his feet. And now, with Selifan gone, the numbness continued and grew. Tchitchikov turned around again and surveyed the beautiful, lovely Jacksonville downtown.