“A pleasant conversation is worth all the dishes in the world.”

-Tchitchikov, trans. D. J. Hogarth

The alarm spoke to the pair.

Tchitchikov produced himself almost immediately to the bathroom to clean up. Selifan was stirred from his sleep, not by his sleeping mate, but by a massive stomachache.

“What did I eat?”

His sleeping mate answered from the bathroom. “‘How much’ is the brother of that question. I believe you ate a pig’s fill of slop. There, two birds, one stone.”

Selifan moaned. “This may be the death of me.” He adjusted himself to a more contorted, unforgiving position so as to produce his brand of comfort. “There we go. How long were we up?”

“Until the wee hours of nine,” Tchitchikov replied. “Serves you just as well, that spiteful hunger. ‘House and home,’ right? There is a fresh saying here, I suspect.” A thought hit Tchitchikov and he peeked his head out of the bathroom, concerned. “And you drove back like this?”

“No no no,” he said. “Well, I do not recall.”

“How much did you drink?”

“Half a bottle of grape soda,” Selifan said. “I think I should stay in bed.”

Tchitchikov approached his poor, food-humbled friend. “No no no, we cannot afford to do that.”

“Tchitchikov, but I am sore and miserable.”

He grasped Selifan’s arm and tugged him. “No, you are unwieldy and unyielding.” Tchitchikov relented. “Come on, now. You will feel better on your feet than twisted into a pretzel in bed. I do not understand how you suffer through those positions of yours.”

“Suffer, yes, that is the word for this.”

“We have much work to attend to. There is the matter of Whittaker, for one.”

Selifan groaned. “Yes, that is true.” He laid one foot upon the floor.

“Good, I see I pulled some sense from you. I have emailed Whittaker for an appointment this afternoon.”

“I cannot sense my foot. Yet I shall go.” Selifan rubbed his face. “But another five minutes and I shall produce the other foot.”

“Excellent.” Tchitchikov returned to the bathroom. “I shall need twenty more.”

****

Their first stop was the office of Representative Everly of the opposing party. And what an opposition! Unlike his opponents who donned the blue color in politics, he donned the red. That is our first note. But in case that provides not enough distinction, one can say, in general, that his redder party were more dedicated to upholding the virtues of the Constitution, should one listen to their side of the argument on their more frequent and better funded television ads. But, in truth, both parties upheld the Constitution in the same regard: they loved it unabashedly, and would drape themselves in our flag given the opportunity. That is perhaps the most important position to take in today’s modern political landscape. Yet there were skeptics of both parties, and they might suggest that either party was but a different side of the same coin; and skeptics of deeper disbelief would agree it was the same coin, though question the differences of either side.

But enough of that! Of Everly: this much is known not only in his close circles, but in all of Palm Beach County, that he is a businessman. And what is his business, exactly, though he not hold store-fronts on the main road nor heavily-trafficked online shops? He is in the most noble business in our opinion, that is, the business of businesses. Of these he owned a great many, more of such than the average collector of records owns in vinyl products, and as such one could say Everly was one of the luckiest men in all of Florida. There was no type of commerce that his businesses would not deal in, and this would make him seem a jack of all trades, as the saying goes. Yet these businesses were so simple for him to produce and run that oftentimes he would forget exactly to which one you may refer, should you ask directly, perhaps if you were a banker or a member of an enforcement agency. But his truer business, should we better give a sense of him, was people: he was a master of people, of a great many people. As such, he was well-versed in the skills of giving a firm handshake and an intimidating stare, which I must say, are two practical skills necessary to a successful politician. His name was well-known outside Palm Beach, well outside Florida, even so far as China and Italy and Tchitchikov’s childhood home of Russia. Yet he made not a big claim to his international renown, such was his humility, and rather decided to remain local to Palm Beach first and foremost, dedicated to the inhabitants there. His wardrobe was of the finest silks, too fine for most all members of Washington, but if refined taste were his only fault, we should grant him that much.

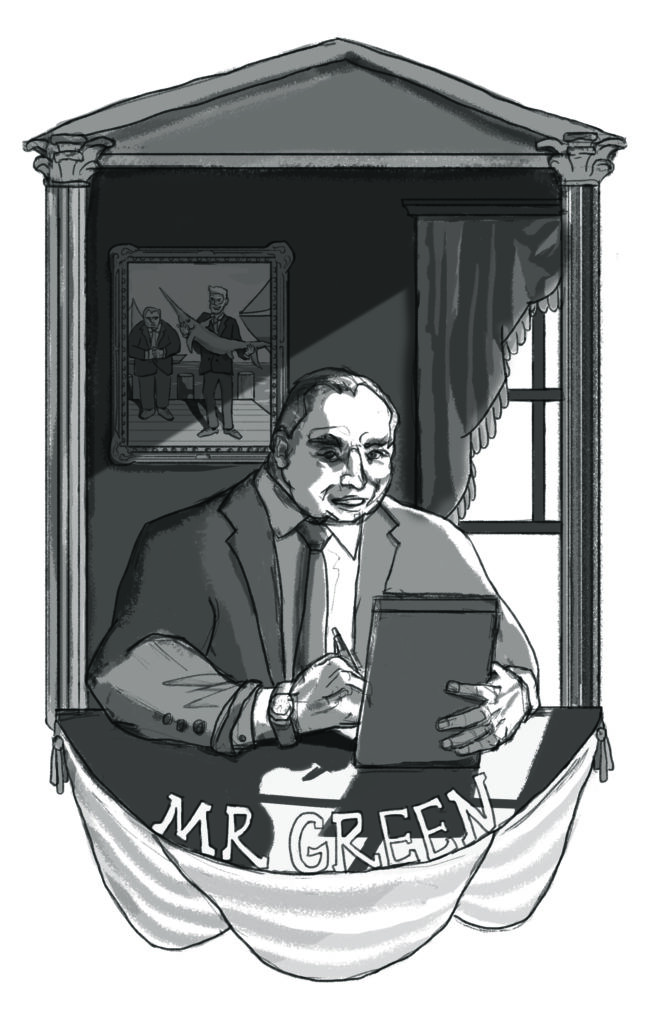

As it were, Representative Everly had left to attend to other business, as happens often to someone with so much business on his plate, and Tchitchikov sat down with Everly’s associate, that is what he termed himself, Mr. Green.

“You are a persistent one,” Mr. Green said.

“I believe persistence a virtue,” Tchitchikov said.

“It leads to success.”

“It leads to fortune.”

The two shared a knowing laugh.

“Well, Mr. Tchitchikov—the name rings a bell. Maybe first you should tell me if you have relatives in Russia.”

“I do!” Recently, Tchitchikov had an ache to speak of them. “They are poor farmers, and I do miss them dearly. I remember but vague images of our farmstead now, and of our few livestock.”

“They’re not in the oil business?”

“They are no oil tycoons,” Tchitchikov said. “They certainly do not deal in oil, save for their heating.” “Oh,” Mr. Green said. “Please excuse my confusion.”

“That is alright. Now, to the business at hand.” Tchitchikov produced his hand-soiled notebook. “I have access to a great many voters and their ears, among other political parts of them.”

Mr. Green laughed. “Sorry, I was thinking of a joke. But how many?” He smiled. “And which parts?”

Tchitchikov replied, “A total of nearly fourteen thousand in the state, and a little over one thousand in this county. And I have access to their votes, we shall say, almost directly.”

Mr. Green took careful note in his pad. “Just a thousand?”

“Well, yes, but their votes are nearly guaranteed.”

“Nearly guaranteed?”

“Exactly guaranteed.”

“And how so?” Mr. Green asked.

“Their votes, unlike their bodies, are quite alive.” Tchitchikov smiled. “And those same votes are at the ready of my fingertips.”

“I see,” Mr. Green marked again in his pad. “I should be blunt, Mr. Tchitchikov.”

“Yes, please do.”

“Mr. Everly has won his last election with nearly ninety-five percent of the vote.”

“Why yes,” Tchitchikov said. “But he had no challenger last time.”

“And as to the challenger this time, we feel he shall not win.”

“But the polling suggests that the race is far closer than you suggest.”

“Yes,” Mr. Green said, “but our internal polling suggests it shall be a landslide in our favor.”

“How is that?”

“Never mind how is that,” Mr. Green said. “But let us say that we are exceptionally confident in predicting how this election will turn out. Our polls are very accurate, I assure you. I thank you for your time, Mr. Tchitchikov.”

The two shook hands, and Tchitchikov felt his strong, strong grip, as if he might have wrestled oxen in a former occupation. Our tale’s hero left and glanced at the parking lot in surprise: Selifan was gone.

“Where the blast is that…?”

But as it was a rather lovely day, Tchitchikov went for a walk to calm himself. The heat was stifling in comparison to his childhood Russia, but he had acclimated to that, and the different culture in our free country. Still, sweat beaded upon his brow, and he was unused to such an extended exposure under the beating sun. He sat himself down at a bench and gazed upon the bustling beach nearby. Bikinied women lay on the sand, and muscled men patrolled the area lazily. A volleyball was hit about, and a few fellows with frisbees tossed their bright discs to each other. Despite the interesting people-watching, Tchitchikov mulled over his dreams of wealth and power within the District of Columbia. They were still there, these dreams, and his heels still clicked in those fabled halls, but strangely his mind drifted off in the direction of his innocent (somewhat) motherland Russia. The playful chums and simple games from a simpler time. The rough, hard work his father did in the field. His calloused hands as they tousled his hair and administered discipline. And his fair mother, also in some ways harsh, but he saw now to prepare him for the far harsher world. He slowly drifted back onto the bench, before the ocean sloshing itself, and meandered back to the parking lot of Everly’s office.

Selifan’s car had appeared in his absence.

“And where were you?” Tchitchikov asked.

“I went for a brief respite,” he said. “I did not realize you would sell the souls so quickly.”

Tchitchikov shook his head. “Everly is not one to need them.”

“Why is that?”

“For I believe they have other phantoms to count on. Come, let us eat.”

****

Friday was fried fish day.

Selifan had his cheeseburger—no relish, no pickles, no mustard, ketchup and tomato only—while Tchitchikov dug into his portion of fried cod, neither base nor majestic. The shush of waves abated from the beach near the seafood stand. He foisted the fries upon eager Selifan; they were, he would not say but thought it, too plebian for his tastes.

“Another email,” Tchitchikov said.

“From whom?”

“O—. She’s a nice, polite person,” Tchitchikov said.

“Strange,” Selifan muttered.

“Strange what?”

“You made a kind, honest word of her. It is strange to hear that.”

Tchitchikov frowned to himself. “You may be right, for it felt strange of me to say that.”

“And another strangeness.”

“How so?”

“That you note her politeness, and not mine.”

Tchitchikov took a large bite, as an untamed predator might. “Selifan, it is not that I do not note your finer qualities. It is that I am terrible at vocalizing them.”

“I noticed.”

“Then do not doubt of them, but doubt of my own abilities.”

“Sometimes I do.”

“Very well, then.” Tchitchikov took another large bite of fish, sea lion-sized. “That is fair. But let us focus on the task at hand.”

“Yes, we could.” Selifan doused his burger in further ketchup. “Should we revisit with Taber? Should we make our first appearance to Stoddard?”

“Whittaker returned my missive. We shall make our stop there.”

“Fantastic!” Selifan attempted a clap, but as his hands were also doused in ketchup, he rethought the reflex. “Then we shall likely hit paydirt.”

“Possibly,” Tchitchikov said. “But I would not aim for it. This is a first contact, and we have to size each other up initially.”

“I see.” Selifan finished his burger and struck into his fries. “Still, I am excited to hear what we turn up.”

“As am I, Selifan.”

****

M—, Whittaker’s aide, welcomed Tchitchikov to a seat in Whittaker’s office. “Just a moment,” she said, smiling.

Tchitchikov nodded and waited. M— engaged in idle conversation, with what some might even term flirtatious chit-chat. “I like that vest on you, Mr. Tchitchikov.”

“Why, thank you.”

“It looks as if you have a pocket watch. I love pocket watches.”

“No, just the one on my wrist.”

“Oh.” M— returned to her work for but a moment. “So, your mother liked azaleas?”

“Azaleas?”

“Yes. You mentioned them a couple days ago.”

Tchitchikov bit his lip in consternation. “Oh yes, she was fond of them indeed. I am surprised at your adept memory.”

“Why thank you,” she said. “I love them, too.”

Tchitchikov smiled brightly to her. “When do you think the Senator might arrive?”

“Oh, he’s here. He’s just in a meeting.”

“Yes, but then when might the meeting end?”

M— checked her computer screen for the time. “Soon,” she said, in that perfect secretary’s vagueness that the cunning would pick up to mean “he is well over time.” “Soonish, I think,” she said.

Tchitchikov glanced at his watch. He was annoyed with the “soonish,” and did not quite pick up upon M—’s subtler context. “Okay. Soon, I hope as well.”

M— smiled uncomfortably. “Yes, but—!”

“But, yes?”

“But, perhaps,” she struggled for words. “Did you notice? I don’t have flowers today, but…”

“But?”

A remembrance of his interaction with M— had escaped him up until now. Normally, our hero would never have forgotten such important details, for indeed therein lies God and true company and, should one seek it out, wealth from such company. But ordering the events of the past four months, and especially those of the past night up until this moment, had fogged his brain into a confusion. Thankfully, the fog of his mind had cleared just in time to save their conversation.

“I mean, but perhaps the purple dress on you now is more lovely than the one last time. I suspect you are enamored of the color.”

“Thank you. You look nice as well,” she said, slain much as she had been last time.

A curious thing, then, to be young and to be wooed! How difficult a thing love is to navigate, and how unsure we are of the other’s feelings and motivations! Love can be a battlefield, the difficult strategies, the fog of war—perhaps I am getting carried away. But maybe it is a battlefield indeed, stratagems and traps laid before us, spies in our midst, sowing misdirection. Tchitchikov might be one of those clever spies, in my metaphor, though perhaps before I get too metaphorical I should clarify that M— was an earnest, young woman, and he, a man who knew how to get what he wanted. The simplest terms are often the best.

“I wonder if you could nudge Whittaker so.”

M— flushed. She was torn between her loyalty to Whittaker and her growing fondness of Tchitchikov. Thankfully, before she dialed the phone, Whittaker came out to the desk. He had brought a warm smile and the faint aroma of whiskey, as it was Friday, though the sight of Tchitchikov evaporated one of those two.

“And who might you be?” he asked.

“I might be Paul Ivan Tchitchikov.” He stood and offered his hand in a friendly shake.

To which Whittaker offered an unfortunately brusque handshake. “And?”

“I emailed you about our meeting.”

“Oh.” Whittaker checked his watch. “I am sorry, but my meeting ran over time, and this next one I must get to.”

“My apologies, is that so?”

“Of course it is so,” he said. “M—, could you please block off the next hour?”

“Yes,” she replied sheepishly.

“Well, Mr. Chicha, it was nice to meet you. Perhaps another day.”

“Perhaps,” Tchitchikov said. The Senator left again, neither hurried nor slow to his office.

M—’s cheeks flushed even redder. “Mr. Tchitchikov, I am so sorry. I didn’t—I—I’m just really sorry.”

Tchitchikov took in the whole of the scene and was too polite to ask her if she had set up the meeting to the Senator’s agreement. “It is no bother. The Senator is very busy; I shall come by perhaps another day.” He gently lay his hands upon the desk. “When might be a better time to come by?”

“Yes, of course!” M— pulled up the Senator’s calendar. “I’m sorry again about today. I cannot guarantee, but perhaps he might be open next Tuesday?”

“What time might he perhaps be open?”

“Three to five. I cannot guarantee, of course, that he will remain so, but I will see to it he knows you are here.”

“That is all I ask.” Tchitchikov nodded once to her. “Miss M—.”

As he turned to leave, M— uttered excitedly, “Tchitchikov!” as a sneeze, almost. “Mr. Tchitchikov.”

“Yes?”

“Maybe, if you were open tomorrow, would you like to…?”

Tchitchikov judged what his Saturday would look like: reading newspaper obits, aligning them with his voters’ registration lists, entering those alignments into—

“I am sorry,” he said, “but I do have a busy Saturday ahead of me.”

“Of course,” she said. “And I suppose Sunday—”

“Is also full. My apologies.”

“I see.”

“But I shall see you on Tuesday,” he said. “And I look forward to the next lovely dress you will wear.”

****

Tchitchikov’s electronic missive to Representative Taber went this way:

Dearest Representative,

I must firstly apologize for my much too long absence. My sincerest apologies, dear friend!

Allow me to respond to your prior communication as such: yes, I would indeed enjoy further sharing of our time together. They say a first impression is a large one, but I suspect the old saying lies in this error, that I do hunger for another meeting for to repeat of my gentle first impression. As to our business, yes, we may discuss this further as well, but let us not be so bold as to think that it should be central to our rare time together.

I am traveled much, and as I am much traveling as of now, perhaps we could rejoin this Monday at six? I know this is after hours, but it will allow us a freer time to get to know each other. I have marked that time, in case you should be amenable. Or perhaps Thursday afternoon should work better for you, though I am unsure exactly of the time I may be open.

Let me know either way.

Sincerely, your friend,

Tchitchikov

He clicked the send button, and off it went. Next, Tchitchikov sent another missive out, this time to Representative Martinez, of this nature:

Dearest Representative,

I must firstly apologize for my much too long absence. My sincerest apologies, dear friend!

But let us catch up and discuss the finer details of our business of the prior meeting.

Sincerely, your friend,

Tchitchikov

Another click of “send,” and this one went off as well.

Tchitchikov paused for a moment. He felt he had one other piece of business to attend to.

Dear O—,

Thank you again for

At this moment, he received a mail from Taber.

“My, that was sudden.”

“What was sudden?” Selifan asked.

“One moment,” Tchitchikov said.

Dearest Mr. Tchitchikov,

Our first impression was indeed a pleasant one. Yes please this monday would suit me well. At three. Such-and-such a bar works best. Please do be ready to produce exact proof of what we discussed.

Your dearest,

Thomas I. Taber, III

“And that was rushed as well.” Tchitchikov smiled his hyena smile. “That is good news.”

“Good news about whom?”

“About Taber,” Tchitchikov said. “A quick reply is necessary.” He thought a moment. “Tomorrow.”

“Ah, that putty-man. Very clever work.”

“Yes, I do appreciate the recognition.” Tchitchikov typed up the interrupted email. “But one more piece of business.” He wrote and stopped and rewrote. He conjured words, and dissipated them again. He plotted a more precise trajectory, and yet, it failed to hit the mark. After much deliberation, Tchitchikov found what to say:

Dear O—,

Thank you again. You are a generous soul, and one worthy of this openness. I enjoyed your words last night, and hope these do not bring you to a shock. But that I doubt, for the truth cuts through and does not cloud our recognition of it. Good luck to thee and your Representative,

Best,

P. I. Tchitchikov

“Is that it, then?”

“Yes, Selifan. Let us retire. This was a full day.”