“The love of acquisition, the love of gain, is a fault to many.”

-Gogol, trans. D. J. Hogarth

Ring, oh Muses, ring the bell of Tchitchikov’s cell phone alarm! Let it sound through the hotel room, ring upon the deaf pages of Tchitchikov’s pocket pad resting on the bureau, dance upon the waters of his tepid gin glass gemmed with air bubbles and upon the tint of an unflushed commode. How it howls now, when last night the television were the only voices and only lights in the room, it Made in USA, Assembled with Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese parts. It lit up the previous Tuesday night much like any other weeknight, quiet like one of the lovely, modest domicile scenes across our fair, beautiful country, interspersed with informative drug commercials and patriotic political ads. Let this ring shrill into Selifan’s tender ears, that I see his face frown gauging the work that lay ahead, beads of sweat perspiring upon his semi-youthful brow. Perhaps these tremors are remnants of a nightmare, one consisting of those dead souls rousted yet to weigh in on deciding our current justly leadership; or perhaps anticipation of a day of fruitful production, sweat accumulating to join his chauffeur’s later toil-water under his heartening labor, under the unending sun’s glorious benevolence. May this clarion rouse our two champions from their slumbers and into the fray of political lobbying!

Already we see Tchitchikov’s inimitable twitch, a wrinkled eye spasm joining his fair neighbor’s toes kicking about, our two heroes, tightly squeezed in one bed, head-to-foot and foot-to-head. This should speak to their mutual respect and love of one another, and it does, though I must admit, should I be in their financial conditions, one such as I might look upon this as an attempt to skirt unnecessary expenses and comforts. But one cannot pass one’s own judgment upon these fair two! Does the law not say, “Innocent until proven guilty?” Does God’s law not say, “Judge not lest ye be judged?” Are these not the tenets by which we abide, until the appropriate governing bodies vote on amending these two later in their legislative sessions— perhaps three months from now, should legislative calendars be held to some semblance of veracity? Then we shall not judge these two on their financial hardships, but on their bondage of brotherly love. And should a love be more than brotherly, more romantic than that, so be it! This is the era of free will, of God’s love eternal, and gays may ever be gay at least until the next legislative calendar update!

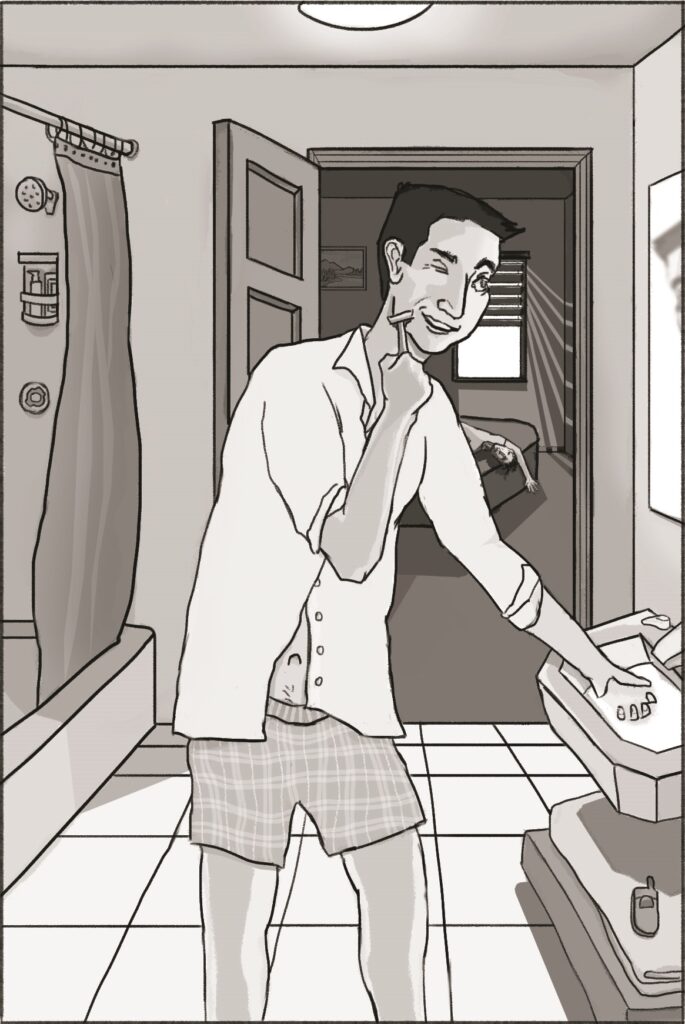

Already we have missed him awakening—Tchitchikov is rinsing his face, preparing it for his morning shave. His blue eyes he may not notice—but we may notice—though they are not anything out of the ordinary for blue, neither sky-blue nor ice-blue, one can only say, just simply blue. Of his hair, one can say slightly more about that, though not by much: this is dark-ish, one can say, and neatly trimmed. His face, though, is clean, and that is the most remarkable thing I can say about his visage, though there is perhaps too much importance put into simply a face. No, there is more, there are secrets and capabilities that a face cannot show. This secret he has kept to himself for the many long years of his middle-aged life: he prodded his cheek with his tongue, poking it out, rounding it for his nearly vintage safety razor to nip at the errant follicles. No cream, just water and several careful swipes at it. That is his secret to a clean, healthy shave, that and not having the constitution to support a full beard.

Selifan stirred from his slumber as well, and his head hung off the foot of the bed in a position of discomfort, yet, I can say that Selifan was the type who was most comfortable when he felt uncomfortable. Like his companion, his constitution was not given to full beard-growth, perhaps less so than Tchitchikov, yet he took it upon himself to sprout a small handful of wisps upon his chin and upper lip in the hopes that, one day, those pioneers would be joined by ranks of their own fellows. That is not to say he is contrarian, or argumentative. Not in the least! His intents are more noble than that, for, like the giraffe who stretched his neck to reach the tallest tree, and hoped that his stretch would pass down to progeny, Selifan hoped, too, that his struggles with facial hair would yield hirsute fruit and pass down to his yet-to-be heirs. But that is as they say none-of-our-business, and not central to our story nor their current states of mind.

As we grow closer in feelings to those we travel with, so we get to know the other’s foibles and faults, and thus, concomitant with their aforementioned brotherly love comes brotherly disagreement. Selifan’s head bobbled over the edge of the bed. He spoke the first words they exchanged in two days. “They’ll have our heads,” he said glumly.

Tchitchikov was not one to be taken from a good, honest shave. He resumed, as did Selifan from the bathroom threshold. “Did you not hear me? Though perhaps that razor should do the job first.”

Tchitchikov pulled his head up from the sink, water dripping off his now-clean chin. He was not quite satisfied with his work, though he should have been, for it was indeed a fine shave he had performed. “Perhaps,” he said. “Though a safety razor, that would be a novel way to perish.”

“The thing seems nearly a hundred-seventy years old,” Selifan said. “When you’re done with your morning beautification, could we address the issue of a small but impressive handful of people desiring our heads detached?”

Tchitchikov hummed to himself.

“Or something else stupid is on your mind.”

“I wonder what price these names could fetch,” Tchitchikov mused. He turned to Selifan. “In the right hands, they are quite valuable.”

“As are our heads, in our hands. Or rather, still on our necks. Could we consider those two first?”

Tchitchikov examined his fine work in the mirror. He wanted to poke his tongue in his cheek to further determine it finished, but he was self-conscious in front of Selifan. He pulled a cheek closer to the mirror and rolled his eye canted to better observe. “With the right contacts, we shall be immortal.”

“The fountain of youth? Sounds fantastic.”

“Unkillable, or better, even.” He tightened his cheek in a near-smile. “You jest, but I do not. I confess: we have power here. Real, true power.”

“Yet not the power to save our hides. You should consider that money doesn’t buy a pair of resurrections.”

Tchitchikov turned to the other cheek and semi-smiled in the mirror for his next swipe. “There is only some truth to that. Still, my confession isn’t complete. You do realize what this list means, right?”

Selifan left the threshold. “I’m leaving,” he said, picking up his scattered things.

Tchitchikov poked his head out into the room. “We can sell elections here.”

Selifan shook his head. “Idiot.”

“That is the power we have gathered.”

“Of course. Certainly.” Selifan was nearly gathered, himself.

“Selifan, please do not leave. Allow me to explain. These are empty votes. Votes that are guaranteed to the right bidder. All we need to do is find similarly empty legislators.”

“And, again, explain how to keep certain pissed off county party officials from, one, catching wind; and two, leaving our hanged bodies to swing in the wind.”

“Any lawmaker can protect us from chatty volunteers,” Tchitchikov said. “That is the nature of power. It protects power, fool.”

“Thank you.” Selifan slung his backpack over his coat and picked up the canvas bag that held the other half of his road-tripping contents. “Who’s going to buy these supposed votes from us? Who is conscience-less enough to buy themselves an election?”

Tchitchikov stared at his friend.

“Okay, but how will they avoid scandal and jail?”

Tchitchikov stared at his friend.

“Yes, but how will we avoid scandal and jail?”

“Dear, dear Selifan,” Tchitchikov’s tone took an admonishing color, as though he were addressing a foolish child, “you have heard of Washington, D.C. before, yes?”

Selifan lowered his canvas bag. “But that, that’s insane.”

“Aim high, friend. We’ll still hit a worthy target even if we miss the first few.”

“Okay, but,” Selifan unslung his backpack. “Who’ll protect us?”

Tchitchikov returned to the bathroom and addressed the mirror. He poked his tongue again. “This is Congress. One hand washes the other.”

“Yes, true, but…” Selifan sat down on the bed. It creaked under him. “When will we start?”

Tchitchikov was finally satisfied with his shave. He proceeded to roll on deodorant, the third to last step of his morning ceremony. “When I am finished cleaning up.”

****

Oh, how rife with the good common life a gas station may be! It is one of the few intersections of interesting and boorish, of rich and poor, or rather, not rich, but those better off than poor, for the rich are more likely to be driven and to have their vehicles taken care of by people worser than they. But an intersecting place nonetheless!

Selifan pulled his car in front of the gas station pump and Tchitchikov came out to fill the car with gas, the common law abided between one who lacks a car and one who doesn’t. Across from Tchitchikov was a man of, let’s say, should one be full of discussion, they are verbose; this man was such. Then one full of scent, and a scent not entirely pleasant, we should call this person scentful to be polite, such as this man was, to the point that the acidic smell of gasoline was a godsend. As this man were the former, he produced the beginnings of conversation:

“Beautiful day. Fucking love Fall.”

As this man were the latter, to say scentful, Tchitchikov avoided these conversational beginnings as a cat might avoid the miserable sensation of water and wet fur. But when it rains, it pours, and even a clever cat as well trained as Tchitchikov could only dodge so many soft bullets such as they seem. The man continued, holding more aggressively a tone. “Fucking love Fall. Smells so good.”

The irony of the comment did not escape Tchitchikov’s ear, but, rather than goad the specimen, he decided the easier road would be to engage lazily like a half-asleep tortoise. “Yes. The smell. Yes.”

“Fucking love it,” the man said.

“Yes. It seems that way.”

“Could I bum a smoke?”

The man smiled and revealed coffee-stained teeth, should the coffee be scant of milk and full of sugar. “I’m sorry, I don’t smoke,” Tchitchikov replied.

“Why not?”

It was Tchitchikov’s turn to smile. “Let me pick you up one,” he said. “One second, friend.”

Tchitchikov entered the station convenience building. Should the gas pump be rife with lively commoners, the convenience store then was their hive, crawling with several segments of tittering life. Scentful smells of soon to be devoured egg sandwiches and pizza slices wafted through, as well as the aroma of over-toasted coffee grounds. Tchitchikov asked for the bathroom key and, on his way, clumsily brushed on the candy rack with his sleeve, spilling a handful of chocolate Sancho Peanut bars onto the ground and continuing.

“Hey,” the cashier yelled, “don’t go knocking things down!”

Tchitchikov paused and looked down at the mess behind him. “I’m sorry,” he sounded flustered. “I didn’t see them.”

The cashier glared.

“I’ll get them,” Tchitchikov replied, and bent over to pick them up and replace them. “Sorry,” he said, finishing and returning to go to the bathroom.

He stood in front of the mirror, smiled and grinned and smiled again. He looked at his watch. He breathed on it, buffed off the condensation, and ticked his head like a soft metronome for a few beats.

He left the bathroom and approached the cashier. “Pump two,” he said.

The cashier gave him his change and another dirty look. Tchitchikov looked out the window to the man at the pump. He smiled to him. Tchitchikov pointed to the cigarette rack. “Sorry, how much are these?”

The cashier pointed at the rather obvious signs on the racks. “Never mind. I don’t smoke; no need to start now. I’ll take a paper,” Tchitchikov said. “No, the local one.” He left the building. The man at the pump followed him with his eyes and his full-blend coffee smile as he walked past and opened the door to Selifan’s car and hopped in.

“Here you go,” Tchitchikov tossed a Sancho Peanut candy to his friendly chauffeur. “We’re making good time.” He opened the newspaper.

Selifan peeled the topmost of the candy and wrapped his hand around it and the steering wheel. He scooted his seat forward another inch and his knees nearly cradled the steering wheel, that is to say, he looked rather uncomfortable, though, as aforementioned in our previous scene, this was comforting to him. They left and he cleared his throat. “How much do I owe you?”

Tchitchikov flipped to the obituary section of the newspaper. “Same as last time.”

“Then how much did it cost?”

“Same as last time.”

“You do realize I’m out as soon as you get caught. How much do you figure bail would be for a two-dollar candy theft?”

Tchitchikov hummed to himself. “The delightful Duval County has yielded another forty-one votes for us. Delicious.” Tchitchikov pulled out his notepad and licked his pencil. “Don’t worry, no one we know. That makes a rough total of three-thousand, three hundred and,” he licked his lips, “seventy-two. Seventy-three. A state total of thirteen eight-hundred twenty-one. Thank you, Duval County.” Tchitchikov held back a sneeze. “And bail would be the same as last time. Easy calculation, that one.”

“Next calculation: how many people are in Florida?”

“Twenty-one million.”

“What does not quite fourteen thousand votes matter, then?”

Tchitchikov shook his head. “Wrong question, first of all. The better question is ‘how many people are registered to vote state-wide?’ Thirteen million. ‘How many cast a vote?’ Eight million. ‘How slim are the margins?’ Now that, that’s the best question.” Tchitchikov rolled down his window to get a fresh breath of the overly sunny air. “Six years ago, almost to the month, our fair incumbent won this state by a mere thirty-one thousand, six-hundred votes. A razor’s edge, compared to a pool of a few million. Now, our fourteen thousand votes look the substantial prize, don’t they? And, unlike our generous heapful of gerrymandering and ID laws, getting the dead to vote for you is a one-hundred-percent in-the-bank solution. It’s about as reliable as printing money. But better. We’re printing power.”

Selifan frowned. He looked uncomfortable, twisting his neck and face in a position comfortable to him. “Yes, but you just said that Whittaker won by thirty-one thousand votes. What if this time around, he needs thirty-one thousand to win? Our fourteen won’t cut it, then.”

Tchitchikov shook his head. “We can’t harvest all the dead here. It’s about playing each angle at percentages. This angle yields the best percentages.” He shrugged. “If Whittaker doesn’t win, we still make our bank. And if he does, though, and he recommends us to his friends: well, now we have capital and customers to run our business.” He took a deep breath of the beautiful air. “Isn’t it glorious outside?”

“You’d think reading the obits for the past four months would get you depressed. I wonder what that would take.”

“Reading the obits the past four months and not making a dime at it.” Tchitchikov stuck his nose out of the open window. “Let’s do it. Let’s plant the first seed of our sale. But first, let’s get in one more loop of this beautiful Florida sunshine.”

****

Senator Whittaker’s district office was in, not quite the heart of Jacksonville, but in a far nicer, cleaner area near a few large parks and small shopping centers, on such-and-such a street near such-and-such an avenue. It was a lovely, humble office, neat and clean and professional and producing mainly of gentle whiskey socials on Fridays. There were pictures of the Senator shaking hands and smiling with local stars, such as the lead actor on a large action movie, the movie but three years old; the Senator shaking hands and smiling with an international pop singer, one who might be called a one-hit-wonder, in terms of her song charting in the States; shaking hands and smiling with a recipient of recent a Nobel Prize, we shall not name which award as to hide their identity, but consider it in the field of either science or math or literature or otherwise; and the Senator most graciously shaking hands and smiling even wider with his fellow party officials, some of whom Tchitchikov recognized from certain alleged money laundering scandals of days past. These and other such photos decorated rather fine pieces of furniture, tables from a local designer, desks made of teak, so as to remind one of the more extraordinary possibilities of life. The ambience of the office was, to be truthful, very much in line with Whittaker’s personality and under its breath it whispered its agreement nearly literally.

His aide’s first name was M—, we have removed her full name at her request, and M— was a native of Florida for the majority of her twenty some-odd years. As a native of that state, she was used to the sun’s limitless rays, shining down upon her over-tanned arms; to lizards everywhere, stampedes of the small things at the most inopportune and hilarious times; and less humorously, the mincing out-of-state elderly, whose seasonal habitation was Florida from October the first to March the thirtieth, or some variation of nearly six months. They came from Rhode Island or Massachusetts or some other cold, Godless, potholed New England state, and resided there no longer than six months and one day. M—, then, was happy to make acquaintance with our charming Tchitchikov, he being at least twenty-five years junior to the average constituent she usually dealt with, and he seeming that he would produce about a dozen points less blood pressure than she was used to. “How may I help you?” M— asked Tchitchikov.

“I’m curious if Senator Whittaker was in,” he said.

“And who might you be, please?” M— smiled to him.

“My name is Paul Ivan Tchitchikov—the last name starts with a tee, the rest sounds itself out—and I live at such-and-such a road in Jacksonville. I wanted to ask the fair Senator if he were interested in speaking to our congregation the Jesus on High.”

“The Jesus on High?”

“Jesus on High,” Tchitchikov corrected, “and we are, I’d say, an intimate group of about fourteen thousand praying, shaking souls to bring God’s word upon this lovely planet of ours. If the Senator could make a brief acquaintance with myself, in regard to his personal faith and how he has found God in these heathen times, then we could—”

“I’m sorry, what was the website you said? Jesus on High?”

Tchitchikov stared at her. “Website?”

“Yes, so I can do a little research.”

He blinked blankly at her, and the expression “grew two heads” might seem appropriate for Tchitchikov’s stare. “Miss, young Miss M—, we don’t have a website.”

“Yes, but how do I—?”

“I am, and I hope I don’t overstate myself in any way, a fair amount of research standing before you. We believe in two things: in human-to-human communication, one; but firstly, in Jesus on high.”

M— wrote furious notes. “‘Human to human…’”

“Soul to soul, more accurately, but I don’t like to impose our sentiments upon others, not until they’re ready. Yes, you can erase that.” Tchitchikov bent over her desk. “Yes, ‘soul to soul,’ I like that better. Thank you.”

Tchitchikov continued. “If the Senator has some time, and really, a brief five, ten minutes is enough for me to get a sense of him, then we’d better be able to weigh the Senator’s faith and how his guidance might help us glide through these challenging times. We would love to hear his plans, if he wanted to address our congregation.”

“Hold on,” M— kept scribbling. “I think I almost have it.”

“Here’s my contact card,” Tchitchikov produced a simple black and white card, “and if you could leave this for him, I would greatly appreciate it.” M— took the card, keeping her face on the notepad and her scribbling. “You can say ‘work through,’ I don’t think I like the sound of ‘glide through.’”

“Okay, almost done.”

“Thank you, Miss M—, I do greatly appreciate your help.” Tchitchikov turned part-way and stopped himself, returning to M—. “I’m sorry, but I do have to say: your dress. I love azaleas. It’s rather lovely on you.”

Despite the dress having not azaleas, but rather violets on a white background, M— blushed. “Why, thank you.”

“Azaleas were my mother’s favorite. They always reminded me of warm days and warm apple pie.”

M— curled up more into her blush, hit with a soft shaft in her tender heart. “Awww, that’s so sweet! Don’t embarrass me!”

Tchitchikov tapped his foot. His legs, though the aide could not see, signaled impatience, and his face signaled the brightest of the world. Tchitchikov was, one could say, tearing at the seams, and might literally have done so if both his upper half maintained its calmness and composure at her desk while his lower half sprinted away back to Selifan’s car as if from a runner’s block. But a few moments more is necessary, he internally told himself, and externally he told M—, “No need to be embarrassed. I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have—”

“Would you like to come by,” M— paused. “Later?”

“To see Senator Whittaker?”

“I mean, well, I should say,” M— bit her lip. “I’ll let the Senator know. And I’ll give you a buzz.”

“Yes,” he said. “Thank you so much, M—.”

“Of course.”

“I appreciate it.”

“Thank you.”

“I look forward to your call.”

“Yes.”

A few more smiles exchanged and Tchitchikov was satisfied. On his walk to the car, he critiqued his initial rabidity, nearly losing control from his ferocious hunger at the aide’s political access; he had looked like a wolf on its hind legs, whimpering at a piece of meat in a child’s hand, or at least certainly he felt like one. But such is the internal workings of a peddler of smiles, and what a noble profession it is! To bring such boundless joy to those who needn’t even ask for it, to lift others up quickly, very quickly, and to hope they glide gently down after. But the dark side of this type of work is the boundless inner critiquing, which, if Tchitchikov were to publish his endless self-dialog, he might be mistaken for a Proust or a Dostoevsky, at the very least. Perhaps one could mistake his work for a Cervantes, though Tchitchikov was openly more partial to a classic tale of traditional heroism, minus the quirky sidekick; and similarly partial, though less openly so, to the more modern tale of striking it rich, whether it be in mining California gold or mining other people’s investment portfolios. Nonetheless, he was satisfied with the interaction overall.

“How was it?” Selifan inquired inside the car.

“Good,” Tchitchikov replied. “More Godly than I’d intended.”

“God does the trick,” Selifan said.

“God is good as gold,” Tchitchikov replied.

Selifan tapped the steering wheel. “When should we expect a response from Whittaker?”

Tchitchikov stared out at the Senator’s office. “My dear Selifan, that is not how these things work.”

“Then how will you sell him the list?”

“Dearest Selifan,” he said, “you are rather uncouth at politics.”

“What did you say to him?”

“I have yet to say something to him.”

“Wait. What?”

Selifan was one of those earthy, humble fellows whose concerns were more anchored in the physical, the tangible. He owned a car, for one. And his compatriot Tchitchikov, as if Poe were speaking about him specifically and only him, dreamt by day and was cognizant of a great many different things than Selifan. He, for one, was cognizant of the many expenses of a car and opted to find a more earthy, more humble fellow to carry that particular burden of his journey. Tchitchikov, also, had a great many tools in his belt, so to speak, tools such as though he could build a house from nothing, nothing but an apt imagination and a great void in the air. Perhaps that is my love of the generous man and his overgenerous imagination. But, again, I digress.

Tchitchikov explained to Selifan how the meeting went (it didn’t); what to expect (almost nothing); and when to expect it (hardly ever, not without continual prodding). Selifan was, to say the least, determined.

“Okay. But allow me to clarify my concern.” Selifan gripped the steering wheel and took a deep, calming breath. “Pray tell what the fuck you mean you haven’t spoken to him?”

Tchitchikov was unperturbed, gliding endlessly on another day-dream. “We will, we will.”

“How are we going to sell this list without speaking to the buyer?”

“We will, we will.”

“When is that going to be? Are you even listening right now? Is your head so far up your ass you need an extraction team?”

“We will, we—” Tchitchikov broke from visions of mansions and money, from state after state laid in his open palms. “Selifan, please. Have I misled you thus far?”

Selifan stared at him.

“But not too far, yes? We have always righted course again, yes?”

Selifan stared at him and added a glare to it.

“We will be back in a couple of days. It’s important to give both space and pressure. Contradictory, yes, but that is what they call a ‘political pressure.’ Endless nagging over an indeterminate table of time. It’s conditioning them to always be at the ready, even at rest.”

“Okay,” Selifan said. “Then who’s our next customer?”

“Next customer?”

“Yes. Actually, it occurs to me we could make multiple sales on this list. We are selling to more than one bidder, yes?”

Tchitchikov entertained the idea for that it opened the day-dream even further. “Yes. That is a good idea.”

“Then perhaps we offer this list to Representative Fairwell?”

“No, that is not a good idea.”

“And why not?”

“Selifan, dearest friend,” Tchitchikov shook his head softly. “I am not sure where to start.”

“This is his district, yes?”

“Yes.”

“And his last election was a tight one, yes? Tighter than Whittaker’s?”

“Yes.”

“Then he should benefit more from this type of insider’s list.”

“Yes. He could.”

“Then it’s settled! We should go immediately to him. I wouldn’t be surprised if he bought the thing right today.”

“No.” Tchitchikov’s head slowed its soft shaking. When it came to a full stop, it turned to Selifan as if to say, Why are you doing this to me? Why are you perplexing me with something as impossible as asking a domesticated kitten to feast on the lion’s share, a full antelope? Should a fully pregnant sow grow wings within the span of a few hours and take flight these days? Should we truly be friends and this you ask of me? But instead, Tchitchikov’s lips took the easier route and spoke, “He would not take it.”

“Maybe for less, but that’s money in our hands.”

“He would not take it if we gave him money to do so.”

“I don’t understand what you are saying. Is he not political? Is he no politician?”

“Yes, but,” Tchitchikov sighed. “You see, Fairwell is one of those old guard, old school, very, very old school ones, whose beliefs lie in the impractical. He is one to campaign, to legislate, to speak to voters. He might as well be of the mind of one of the country’s founding fathers, which, as you and I know, is antiquated in our modern times. Worthless, no, worse than worthless. It puts a target on his back. And furthermore, he is proud of that fact. It is some colored badge of courage to him.” Tchitchikov shook his head more forgivingly this time. “Perhaps blue.”

Selifan’s knuckles whitened on the steering wheel. His expression spoke thusly, Do you think I can afford to sit about far from home, hotel to hotel, in the hopes that you pull off the impossible? Does money still grow on trees these days? Do you possess one you have yet to tell me of? Should I subdue you into common sense through wit and reason, or through blunt force trauma? He chose the former. “My dear Pavel Ivanovitch, are you not such a man as to have wheedled nearly the whole voter lists of the state for but the cost of a tuneless song?”

“I am.”

“And are you not as witty and hardworking as to have discovered profit from a total of fifty-two dollars and change in newspaper subscriptions from reading obituaries over the course of several months?”

“This is also true.”

“Then, does the saying not go, ‘nothing ventured, nothing gained?’ ‘Leave no stone unturned?’ Is not a politician but a politician, as a wolf must always be a wolf?”

“Yes, but…”

“The two men are the same party, are they not?”

“True, but still…”

“Then we should venture the possible sale. What is there to lose? We are waiting two more days here regardless.”

Tchitchikov found himself nodding through Selifan’s reasoning and discovered his agreement with him. “Yes,” he said, “there is nothing to lose.”

“Good,” Selifan said. “Then let us get going after we get our fill of this beautiful air and sunshine.”

****

Should Senator Whittaker’s office be the height of elegance, perhaps Representative Fairwell’s office, but a few skips and hops and highways away, and closer to the busy and trafficked heart of Jacksonville, would be more than a little dizzied and perhaps nauseous in its presence, should an office be capable of such commonplace emotions. Whittaker’s office, if it could speak, would be loquacious and, some would say, capable of evoking all the emotions necessary to a welcomed guest without the unnecessary trouble of having to parse what exactly was being said. To which Fairwell’s office might reply: rather, we’d not say, but something crude and cutting and very nearly a grunt in disapproval. Still, Tchitchikov made his acquaintance there.

The office, which thankfully was not capable of blunt speech nor disgust at lovely speech, was adorned with simple desks, piles of papers, people sitting at the desks with piles of papers and, if Tchitchikov could see the front faces of picture frames, boorish photographs of family. Fairwell’s aide, O—, whose name we omitted for both our embarrassment of her station in life and also for sake of symmetry with Whittaker’s aide, was harried, overworked, and should have been, by reason of constant contact with what I shall bluntly term “The Great Unwashed,” less amenable and more assertive than she was.

“Hello,” O— said, not looking up. “What can I do for you?”

“My name, fair lady, is Paul Ivan Tchitchikov,” he offered a business card, “and I’d like to speak with—” Tchitchikov decided to undo the error of his previous visit earlier in the day, “Oh, my. I’m sorry, but I am taken aback by those bright earrings of yours. Perhaps they—”

“Thank you,” she said. “What can I do for you?”

Tchitchikov smiled. “Why, I would love to speak to our dear Representative Fairwell.”

“Are you a constituent?”

“Yes, I live on—”

“Take a seat,” she said, pointing to a tight row half-filled with those “Great Unwashed” I mentioned earlier. “It could be an hour or two,” she told him, turning down into her work again.

Tchitchikov surveyed the three remaining seats and made a quick calculation as to next to whom he’d sit most comfortably. After the quick calculation, he made another, more careful calculation, as some decisions in life require a second thought, and after the third, quickest and most subdued calculation, he took the seat in the corner next to a nice, plump fellow. He grinned a near smile to him.

It was a torturous two hours. In that time, he had seen the Representative come out and shake hands with each of the previous tenants of the other seats, which gave Tchitchikov hope of speaking to the man directly. Tchitchikov bemused himself with idle conversations in his head, with personages of high rank and esteem—and who wouldn’t wish such a thing for himself?—of performing beneficial and generous services for them, and receiving but the subtlest commendations and lightest gifts from them. After a wait of two hours and eleven minutes, the disheveled representative addressed our hero.

“Hello,” he said to Tchitchikov. “Let’s head back.”

The two wove between packed desks and Fairwell’s worker bees, as I choose to term them, busy in their nest. Fairwell offered him coffee.

Although Tchitchikov did not drink coffee, he accepted out of politeness. “Thank you, Representative. A warm cup of joe sounds nice.”

“Okay,” Fairwell said, exerting no more energy than was necessary to reply. “It’s right there.” Fairwell stopped and pointed to a small table cramped with boxes plundered of sugars and carafes dripping of milk.

Tchitchikov smiled. He was obligated to oblige the Representative and regretted it. But yet he came upon the table, poured the lukewarm beverage into a paper cup, viewed a slight film of oil, and resumed to Fairwell’s office, following behind.

Fairwell’s personal room—for it was too tight to be called an office—had family photos scattered about, along with a poster of the Three Stooges and a few Lego models, ships from Star Wars. Boxes crowded under his desk, and his chair was in the middle of the room, flanked by partitions on either side. Should some say the “office” was personable, Fairwell’s personality was not, at least neither on first glance nor the next four following. His movements, like his speech, were ineloquent to the point of pain, and indeed, he seated in his chair with a near thud. His hair was appropriately aged gray-with-white, and his face, should we compare to Tchitchikov’s, looked inappropriately aged, more aged and tired than necessary, perhaps from—well, I can only speculate, but from a lack of focus and running in all directions. Such is not how one wins a race, especially a race to the top, as Whittaker was of the mind. No, one must set upon that path directly and early, too, for it is a long race past and over others, and a race that Fairwell was clearly failing at.

“My dear Representative,” Tchitchikov started. He noticed that Fairwell turned to his watch almost immediately and gave it such a longing look that Tchitchikov could have mistaken it for his distant lover. He turned course with the representative, as any capable captain would, and proceeded as such, “Allow me to be blunt.”

“Okay.”

“You have barely scraped through your last election.”

“I know.”

“I may have something of use to you.”

“What.” Fairwell’s question, like his entire demeanor, was flattened.

“I have at my access a fair voting bloc who are, as we shall say, hungry to support a worthy candidate.”

“So?”

The reply came like a light fighter’s jab to Tchitchikov. “All I would ask is a humble donation to—”

“I don’t have money,” the Representative stood up. “And I don’t need votes. The people elect who does the job the best.”

“The polls say your challenger is that person,” Tchitchikov was being ushered out, “and by at least seven points. I don’t think you should—”

“Then that’s their problem,” he said, “and not yours. Hawk your bullshit elsewhere.”

Despite his attempts at a conversation, all of which were cut short, Tchitchikov found himself at the aide’s desk again, and Fairwell grumpily shook hands with the last person there and brought them back. The sun was nearly down. The aide didn’t turn her head up.

“Mr. Tchitchikov, right? How’d it go?” She asked, business affect.

“It went,” Tchitchikov said.

She kept hammering away at a keyboard. “Here’s my card.” She took one hand off it, halving her typing pace, and plucked a business card from a card holder to give to him. “Let us know if we can be of further assistance.”

Tchitchikov left with the card and a foggy daze. He had only felt that first jab. The other hits, no, he certainly did not expect nor even see them from the elderly politician, but he certainly did feel their implications on his psyche and mood. Tchitchikov nearly walked into the door of Selifan’s car, took a step back, and opened it instead, dropping down into the car seat. He mused over the brief exchange, weighed different possible scenarios, and summed up to Selifan the experience in as elegant terms as he could muster, keeping in mind brevity be the soul of wit:

“Well, that was a waste of time.”