“Without a friend, what are all the treasures in the world?”

—Tchitchikov, trans. D. J. Hogarth

The peace between Tchitchikov and Achilles was forged with kibble and carrots.

“There you go,” Aris said. “Yeah, slow. Offer it and he’ll come take.”

Tchitchikov flattened his palm with the last two bites of carrots. Achilles sniffed, then nibbled, then licked the last flavors of the snack from his hand. The ceremony was complete.

“There,” Aris said, “you two are officially friends. He’s more of a lover than a fighter, anyway.”

Tchitchikov sniffed his moist hand. “He seems more of a mouth and stomach than either of those.”

“Don’t even talk about the liver,” Aris said. He finished the final bites of his tuna-on-toast, dusted his hands, and then clapped once. “Okay! Are you up for it?”

Tchitchikov nodded.

“Awesome. I’m so excited! Go take your shower and we’ll get going. You’re going to love it!”

Forty-five minutes later, Tchitchikov and Aris were on the bus toward Fairwell’s office. The lengthy ride was something he was getting used to and even strangely appreciating. He’d forgotten about the woman and her child that he’d imagined on every bus in Jacksonville, no, on every bus on the road. Those two had disappeared from his imagination, and in their place he saw a small family carrying groceries, an older gentleman conversing with an older lady, young men listening to music loud enough that their headphones projected it, and workers nodding off on their way to work. Aris and Tchitchikov greeted Jenna when they arrived and they took their canvassing packets from her.

Aris looked over the packet on their way out. “Oh, you’re not going to love this.”

“What’s wrong? Something is missing?” Tchitchikov said.

“Yeah, Jenna’s mind,” Aris said.

“Well, we can head back for whatever’s missing.”

“No, this happens sometimes. It’s just—” Aris shook his head. “You’ve never been to Happy Oaks Park, right?”

“No, why? I like parks.”

“Not this one. It’s a trailer park. And trust me, nobody’s happy there, either.”

Tchitchikov nodded. “Yes, I’ve heard of those.”

“Of Happy Oaks?”

“Well, no, but of the concept of trailer parks.”

“I’ll ask for another territory.”

Tchitchikov almost agreed but something akin to curiosity struck him at the last moment. “No,” he said. “We can stick with this one.”

“You sure?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

Tchitchikov shrugged. “Why not?”

Aris sighed. “Okay. Here’s the gameplan: stick by me. If things get dicey, just run the fuck outta there. Seriously. I can take care of myself.” Aris shook his head again, as if it might dissipate his incredulity at the territory before them; but the shaking of his head didn’t even disturb his neat hair, nor undisturb his disturbed state of mind. He shrugged as well. “Okay. Let’s do it. Why not? Right?”

On their way to Happy Oaks Park, Aris pointed out the window. “Look, we’re almost there. Let’s meet up at that palm tree if we get lost.”

“Of course, but I don’t see—”

“Actually, if we can’t meet up at that tree, no, fuck it: head back to Fairwell’s. You good?” Aris stared into Tchitchikov’s eyes. “You good?”

“Well, now you’re scaring me.”

“Okay, good. That’s where you want to be right now.” The bus stopped and Aris stood up. “Take a breath: it’s the last breath of fresh air until we get through this list.”

Happy Oaks Park was everything Aris promised of it and more: it was a trailer park. There were, by my accounts, at least two things wrong with the name, but I shall not clarify so as not to scare you, my fair reader! Let us instead recall its far sunnier and happier past: in times of Spanish conquest, the area was home to a small subset of an indigenous tribe who had prided themselves on fishing and the toolmaking for such. The Spanish had heard tales of their fishing prowess from other tribes, and had heard of their peculiar method of diving off their fishing skiffs into the ocean water to harvest their catch, purportedly for hours at a time. The first meeting between the two cultures was cordial to the extent that one of the conquistadors caught fancy of a native woman. Their second meeting was less cordial, as the Spanish inquired as to her price, and their third meeting was their final one, with the Spanish having satisfied their curiosity about the tribe’s ability to withstand the ocean’s waves unaided.

Happy Oaks Park on this Thursday morning was as busy as it was on every Thursday morning, and the Wednesdays before these Thursdays, and every weekday, as well as weekends, too. The hum of air conditioners hummed throughout the mobile home park in those mobile homes lucky enough to have them. Aris flipped through the packet of voters and looked around, then back, then forth, then closed the packet and sighed.

“I hate trailer parks.”

“Where do we go first?” Tchitchikov asked.

“I don’t know. It’s a trailer park. They all confuse me.” Aris gave Tchitchikov the list and pointed at the top. “Here. Number one. No idea where they put it.”

Tchitchikov held the list in his hands. There was something about it, something magical about the mundaneness of a voter registration list.

“Have you seen one of these?” Aris asked.

Tchitchikov nodded his head. He glided his fingers down the columns, the extraneous ones were cut, items such as the years they’d voted, where they’d been registered, only Name, Address, Party Affiliation and other columns for the data they were to collect. Tchitchikov smiled. “Where do we mark if they’re dead?”

Aris looked over the list. “Oh, trust me, some of them are in a lot of ways. Some of them you’ll wish were. Come on, I found the first house. Let’s get going.”

Tchitchikov pointed to a sign at the house, Beware of Dog. Aris laughed. “So Andy told you that story? Achilles didn’t attack shit. But yeah, these dogs here, they’re all crazy. This house is a definite skip.”

It took several attempts to speak to a John Concerned Voter, as most of the mobile homes there had guard dog signs. Eventually he came out. “What do you want?”

“Sir,” Aris started, “we’d like to ask you for your vote for—”

John Voter slammed the door.

The next few mobile homes ended up like this:

“Go away.”

“Don’t need to vote.”

“Not buying.”

“Get a job, you bum.”

“I don’t talk to commies.”

“Am I a commie for telling you to vote?” Aris yelled at the door. “Whatever. We’ve got like fifty doors left, but I think we’ll finish in an hour. Forty-two cee is this one here.”

Tchitchikov knocked on the door this time. An elderly woman with tangled gray locks answered and, face to face, the two were stunned by each other.

Tchitchikov made a vague attempt at conversation with her. “Ummm, Miss…”

The woman smiled and looked around and nodded.

“My name is Paul. I’d like to inquire as to how you intend to vote next Tuesday. Do you have any preference for the Congressional representative race?”

She nodded.

“Great! Perhaps you can enlighten me toward whom you’re leaning.”

She nodded again.

“Fantastic, would it be Representative Fairwell?”

The elderly woman nodded.

“Great!” Tchitchikov looked over the script. “Aris, perhaps you could assist me?”

Aris shook his head. “Just watching.”

“Okay,” Tchitchikov looked over the script, “it says here that we can offer a ride to the polling place.” He looked up at her. “Would you want that? Would you want a ride to your local polling station?”

The woman nodded yet again.

“I am glad to hear it! Let me see. When would you want to be picked up?”

She nodded.

“Right, so you want to be picked up. But what time would best suit you on Tuesday? Morning? Afternoon?”

She smiled and nodded some more.

“Yes, I see we are in agreement, but to clarify—”

“Thank you for your time, ma’am.” Aris tugged Tchitchikov’s shoulder. “Let’s mark her a no.”

“But I don’t understand! I am—!”

“Paul, let’s go. Let’s call this one a learning experience. Next one.”

The next woman Tchitchikov spoke to was younger than her, by age, though not necessarily by wear of life’s experiences. They discussed the race briefly.

“Why should I care?” The woman asked.

“Miss,” Aris said, “we think it’s important to participate in democracy, and to elect the best leaders who are up for the job.”

“Why?”

“So they can pass legislation to help us,” Aris said.

The woman shook her head. Then she laughed. Then she cackled, much as a hyena, nibbles of laughter on the larger carcass of life, until she finally sated her hunger. “Really.”

Aris was stunned. Tchitchikov picked up. “Why, yes, would you not want the most beneficial policies for yourself?”

The woman’s demeanor darkened into a storm cloud. “Let me tell you something. Listen, both of you:

“I have a stomach thing. Like an ulcer, but worse than that. I can’t eat spicy foods, I can hardly eat anything. I went to the doctor, and he laughed me off. This was like, I don’t know, five months ago.” She ground her teeth. “Two months ago, my stomach burst. I was here, watching TV, watching Days of the World, and I tell you, it was the most unbelievable pain you’d ever felt. I’ve had two kids, almost twenty hours of labor each. Worse pain than that; you probably never felt such pain. The ambulance took me to the hospital. They stitched up my stomach. I still can’t eat anything, except now I can only eat less, they cut a few parts out of it. My stomach is so small, I’m lucky if I can have a donut.”

“I’m sorry to hear that, ma’am,” Aris said.

“That’s not even the best part,” she continued. “The ambulance sent me a bill: almost three thousand dollars. Now, how the hell am I supposed to pay that? They keep sending it, and I keep throwing it away. I’m never going to be able to pay that bill. I’m on Social Security. Already that’s gone down. Now let me ask you something: why the fuck on God’s green earth am I supposed to care about—what’s his name?—Fairman?”

“Fairwell,” Tchitchikov corrected.

“Fairwell. Well, fuck Fairwell.” She laughed more viciously this time. “What’s he going to do for me? Pay my fucking ambulance bill? Does he want me to die? I don’t give a shit. Kill them all.” She slammed the door.

Tchitchikov and Aris stood in silence. The woman’s story penetrated Tchitchikov to his core. He’d never heard such a pathetic tale, and had never met someone who was, as she might term it, “totally fucked.” He stared blankly at the trailer door, mucked over with grime and a dusting of green moss, and could not compose any words, let alone thoughts to process what had just happened. But Aris, thankfully, had been able to do so.

“Let’s mark her a no,” he said.

****

“You remember that lady?” Aris took a bite of burger. “I feel so bad for her.”

Tchitchikov nodded over his burger.

“I mean, man, this is why I hate doing trailer parks. So many people are just, well, fucked. Straight fucked. That lady, now don’t get me wrong, she’s definitely kind of nuts. But yeah, still, it’s not fair.”

Tchitchikov put his lunch down. “Yes,” he said, “it isn’t fair.”

“Not gonna lie, but she’s got a point.”

“Hmmm?”

“Remember what she said?”

Tchitchikov sighed. “I did not realize an ambulance was so expensive.”

“No, dude, about the—” he whispered. “About Congress. About killing them all.”

Tchitchikov took a quick survey of their surroundings before proceeding: no cops, no bystanders within immediate earshot, just two kids on bikes likely playing hooky. “What?”

“Yeah, she said ‘kill them all.’ Remember?”

Tchitchikov nodded.

“Well, not gonna lie here, but I want them dead, too.”

This is a moment that I should want to preface—though certainly that is too late, Aris has already spoken—with my views on this belief, that is, to desire of the literal extinction of Congress, these views are such: no. That is not what I want to advocate here, and perhaps Aris would not wish to—

“Dead. Absolutely.”

—then perhaps I am wrong on that account, and should not have spoken for the beliefs of our hero’s friend. Yet, I must again impress upon you the standard disclaimer, dear reader, that yes, although Aris is entitled to his opinion, it is not necessarily the opinion of myself, nor necessarily of Tchitchikov, and that I must vehemently deny murder of said Congressional members—they are simply doing a job they are tasked with—though if one should feel they are not doing their job, nor up to the task, then the offending parties should be summarily dismissed, rather than having their lives rent from them. Violence, I hope, is not the solution here.

“But that’s just my opinion. I’m not far from fucked, myself. Achilles has liver cancer. He throws up yellow bile every now and then. If there’s one thing that’s expensive, it’s dog cancer. I’m not sure how I’m going to pay for the surgery.” Aris looked distant. “Dead: yes. Every last one. I think about it all the time. You know, I’ve never told anyone that.”

“Not even Jenna?”

“Heeeeeeell no, she’d flip. She’s not one to hear this kinda crap.”

“Oh,” Tchitchikov said.

“Anyway, we gotta get moving. We still have to hit up half these places.”

The second half of the Happy Oaks Park canvassing list revealed these inhabitants to the two:

- A young, tattooed man, perhaps younger than Aris, who worked at a local retail chain, and who subsisted (if that) on a paltry wage and even sadder health insurance. He would not have been able to afford any sort of home, or even rent, were it not for the unfortunate circumstance of his mother’s passing and bequeathal of her trailer to him. He admitted, despite the gruesome circumstances, that “I’m lucky to have even this.”

- A young couple, two women, whom had been kicked out of their respective households in their teens due to their preference in gender of love (let us note: such a preference is still legal, thankfully!) and likewise struggled, though they were able to make ends meet. The one was a waitress at a diner, and the other served ice cream at a nearby shop, which, in Florida, is a year-long profession. The diner was less than nearby, and quite a bus ride away, which was affirmed by the deep circles under her eyes.

- An older woman who fed a local contingent of cats on her doorstep (or perhaps trailer-step) and who had no need for people, only for more cat kibble.

- An elderly widow whose wife had passed away, and whose bills exceeded his reduced income, forcing him to sell his house and move into a smaller existence in the world. All of these and more Aris had marked as a clear “no.”

Aris wiped sweat from his brow. “Dude, not gonna lie, but that was depressing. Let’s head back. I gotta get ready for work.”

“For work?”

“Yeah. I’m a maître d’ at this pretty upscale restaurant. Italian is overpriced, let me tell you. And our customers are stupid cheap, too. Bad tips. Let’s go.”

They rode the bus back silently. Aris nodded in rhythm to some unknown song playing in his head. Tchitchikov wasn’t sure if he was thankful for the introduction to those who belong to that unfortunate class, what I had termed some time ago “The Great Unwashed.” But he was sure of an indelible impression made upon him by these hopeless souls, lost and deadened by brutish life, and whether that impression were to temper his soul into something better, that is a distinction that either he or you can make, and one that I shall quietly remove myself from.

They arrived at Fairwell’s office and dropped off their materials. “How did it go?” Jenna asked.

“A trailer park,” Aris said. “What would you expect?”

“What do you mean?” Jenna asked.

“Never mind,” Aris responded. “I’ll catch up with you later. Gotta get to work.”

Aris left. Jenna turned to Tchitchikov. “How does it feel to make a difference?”

Tchitchikov answered uncertainly. “It feels…”

“Don’t let Aris get you down. Did it feel good?”

Tchitchikov didn’t want to disappoint. “Yes.” He nodded.

“Cool! So let me properly introduce you to him.”

“Him who?”

“Fairwell. I heard you two had a bit of a tiff.”

Tchitchikov stiffened. “I would rather not.”

“Well, I would rather you did. You’ll see, he’s really a great guy. I think you two would get along.”

Jenna nearly dragged Tchitchikov outside Fairwell’s office. An elderly woman left, and Jenna knocked on the door. Fairwell appeared from behind the door.

“Yes?”

“Alex, I’d like to you meet Paul.”

“Yes. We have,” Fairwell returned.

The only sound was the steady rhythm of bustle in the surrounding room. Jenna tried again.

“I know. I’d like you to meet the real Paul. He helped Aris canvass today.”

Fairwell’s demeanor darkened. The storm, however, abated in a few moments, and he welcomed them inside. “Okay,” he said.

Jenna explained the circumstances of Tchitchikov’s arrival into the campaign, in lieu of Tchitchikov’s own silence. She entreated the two to converse, and the attempt that came of that was such:

“Russia?”

“Yes.”

“Where?”

“St. Petersburg.”

“I have a friend who moved out there.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes.”

There was an extended pause. Jenna itched to fill the void. “See! You two have something in common!”

“I suppose,” Tchitchikov said.

Fairwell frowned.

Jenna smiled awkwardly. “Okay, well we’re going to get going. Have a good night!” She exited, and before Tchitchikov could follow, Fairwell spoke up.

“Paul.”

“Yes?”

“About our meeting earlier. Last week.”

Tchitchikov made a comically audible gulp.

“It’s okay.”

“It is?”

“You apologized.” Fairwell groaned. “I was raised to accept those. Apologies.”

“Okay.”

“And one last thing.”

“Yes?”

“Listen very carefully. I’m not one to mince words, as you probably know. I choose them with great care.”

“And what are those words?”

Fairwell cleared his throat. “You’re not a bad person, Paul. Remember that.”

Tchitchikov took in a deep, humid breath, and relaxed. “I have tried to remember that. That was some time ago, and my memory is not what it was.”

“Then try harder. Good night.”

****

Afterward, Tchitchikov made his way to Whittaker’s office on the public transport.

Senator Whittaker offered Tchitchikov a glass of whiskey. “Neat?” he asked.

Tchitchikov nodded.

“I’m glad you stopped in,” Whittaker said. “I usually wait for Friday to come around, but this is an appropriate occasion for celebration.”

Whittaker smiled, and Tchitchikov imbibed the fiery drink.

“Are we done here?” Tchitchikov asked.

“Yes,” Whittaker said. “I have your dead souls. Maybe a little more. We are done,” he smiled a crocodile’s smile, “for now.”

Tchitchikov nodded. He made his way past the teak desks, past the glare of M—, who no longer invited his company, and he left to one of the lovely parks of Jacksonville.

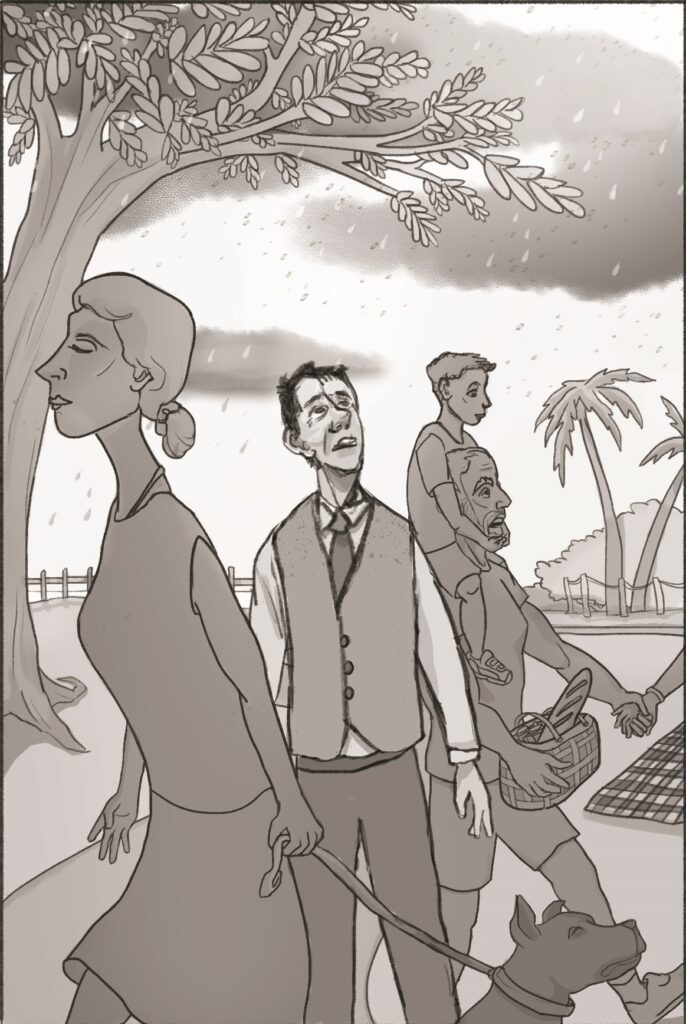

Tchitchikov was, to borrow an overused phrase, lost in thought. Even I could not tell whereabouts he was in his mind, only simply that he was buried inside. His noble intentions were thwarted, his plans teetering on tragedy, and, seemingly, turned against him: the wolf in sheep’s garb was fleeced. (Never mind the quality of the costume’s wool, likely it was a cheap polyester blend from a stingy retail store, but all you need imagine, dear reader, is that wolf with its tail huddled between its legs.) This was the start of Tchitchikov’s troubles, and the initial opening to his labyrinthine stroll through his thoughts. He did not see the couples splayed out upon their picnic blankets. He did not hear the birds chirping incessantly their mockingly bright songs. He did not feel, either, the small sprinkles of rain lightly kissing his now-sunburnt skin.

Yes, my reader, as you have guessed, Nature seemed to sympathize with Tchitchikov’s plight, as we both are, too, I hope, and She started to squeeze her clouds into rain.

The rain did not chill Tchitchikov, however. It pressed his vest and shirt against him, feeling tight like a snake’s skin against his flesh. He walked through the park, the couples now packing up, the dogs heading home with their masters, a cat as well headed back, she participating in a leashed walk apparently, though much more frightened of the rain than the gregarious dogs. Tchitchikov planted himself against a tree, a deciduous and not a palm, and let the large drops fall upon him from the leaves.

And yes, while we could assume the weather was mimicking the internal turmoil of Tchitchikov’s thoughts, let me remind you, this book is one of the realm of life, not of grossly clichéd fiction, and the weather neither felt nor conspired with Tchitchikov’s dark rumination. Rather, the air chilled from its job of oppressing with heat and gave a breath of life to Tchitchikov, in addition to cleansing his flesh, and I would like to say, some part of his soul. His hair fell down upon his face, matted against it, and he simultaneously yearned for a return to his earlier life as a simple postal clerk, and for the return of his simple friend, Selifan.

Now you may ask of myself, this is not action central to the plot. And yes, you would be correct in your perception, my reader. But I include this because we all must, at some point in our time, put aside our dreams, our hopes, our troubles and our pains, and remind ourselves that, yes, we exist in nature, we are part of nature, and that a blade of grass is indeed no less and perhaps even more than the sum journey-work of the stars. We, too, are folded into that journey-work of the stars, and must be humbled, as our kind hero is, to accept these facts as they rush into our consciousness and flee from it in the same breath.

That, my reader, is why we must rest a moment and view upon Tchitchikov, lost in thought and doused in rain.

****

Tchitchikov dusted the couch before he took his rest upon it. He stared up at the ceiling for some time, and then closed his eyes for some time longer. But his attempts at sleep were stifled by the insistent voices he’d heard throughout the day, and then by others he imagined were out there in similarly dire circumstances. He unsettled himself into a sleep far later than he had intended.