“It’s my onion, not yours!”

-Fyodor Dostoevsky, trans. Constance Garnett, from “The Brothers Karamazov”

Welcome, kind reader, to the final chapter of Dead Souls: An American Poem. We hope our journey together wasn’t so rocky that it tossed you from our rough carriage ride; though if you are here, then most likely you have survived the turbulence of my prose and plotting. Yes, there are only a handful of pages left between you and the end of this book, the second section to Gogol’s much more masterful work. I have a few questions for you, and would appreciate your honest replies to them:

- Have you found this novel entertaining? Do you have any particularly favored parts to it?

- Was this instructive? That is to say, morally instructive? I hope more that you find meaning and significance in some of the fiction presented here, more so than in the incredulous scam our fair hero had concocted.

- Should you recommend this journey to a close friend, or a family member?

- Which dish do you intend to dine on post-reading?

I apologize for my imposition upon you, my dear unseen reader! It is doubtful that I will hear your answers from you, and here I am still hoping you shall breathe them into the universe. Yet, for my impertinence, I am of the mind that if we are to follow our timeless hero Tchitchikov, it is imperative that you and I glean something small and of precious value from both our times spent here; and furthermore, that moral instruction is only possible on a full and healthy stomach. Is this what you believe, too? It is no matter should we differ; our differences with each other are many-sized cogs that spin the world together in synchronous harmony.

But I catch myself spinning up another turn of near-poetry. My deepest apologies! We are now at the Tuesday election, and Jenna had left a note on the table for our imperfect Tchitchikov.

You looked wiped, she had written. Hopefully you got some sleep. Help yourself to anything in the fridge.

Tchitchikov had indeed been “wiped,” for it was half past noon by the time he awoke. The day’s voting was well under way. And let it be noted that Jenna and Andy didn’t keep many comestibles in their refrigerator as well. But yesterday Tchitchikov was fueled by several helpings of eggs Napoleon throughout the day, care of Georgina’s co-entrepreneur, and during which day Tchitchikov had completed his masterwork: a massive army of dead souls lead by a phantom command of still lively ones, ones that were likely also to vote corporeally as they had voted the previous three elections. This left no small imprint of satisfaction evidenced on Tchitchikov’s face as he performed his daily shave. He also hummed a tuneless childhood rhyme in his native tongue.

“And Michael, he carried that old hag, and the onion, it bore her weight…”

Tchitchikov sat down at his hosts’ kitchen table. It was another hot, humid, miserable day. He fanned himself with his shirt and declined wearing his too-warm vest. But though the air was thick, it was bearable, for it lacked the pressure of the last few months that had weighed upon him. Events converged, and soon the unknown would be known: the die had been cast.

He brought his items together. A duffel bag, a few changes of now-smelly clothing, a backpack, and a suitcase to hold his laptop. He walked a few blocks to a shady-looking motel, not shady in the cool sense, for it was rather oppressively humid inside; but shady in the colloquial sense, that is to say, not inviting to those who live other than in the shadows of society. Tchitchikov made his acquaintance to a possibly inebriated frontdeskman.

“How much for a room?” Tchitchikov asked the man.

“Roomissixtyfive.”

Tchitchikov nodded. “Could I first make a call?”

The man’s eyes widened.

“Not long distance, I assure you. I want to confirm an appointment first.”

The frontdeskman pulled an old touch-tone phone from underneath the counter.

“Thank you,” Tchitchikov said. He tugged at the cord. “Privately?” He asked.

As the frontdeskman was aware of a great many frightening things in this world that, should he hear of them, these things would make himself far more vulnerable than not, he decided it best to let the mystery go past him. So he said, “Nocashinregister,” nodded once, and walked to the other side of the room, still within earshot, the truth must be told, but he busied himself in a three-year-old magazine of women’s fashion.

Tchitchikov grinned at the man, who was authentic in making himself seem rather engrossed in his magazine. Tchitchikov dialed and spoke, “Hello, is this the Gainesville Sun Obituaries?”

A man answered. “The obits? Sure, let me transfer you over.”

“No, wait,” Tchitchikov said. “I misspoke. I mean to say that I have an unusual occurrence that I would like the Gainesville Sun to investigate.”

“And what is this unusual occurrence?”

Tchitchikov produced his notebook. “I was informed that Mr. G— B— of thirty-seven such-and-such a street had complained that he had already cast a vote.”

“Democracy. And?”

“Well, yes, but that he had never visited the polls, nor cast a vote from his person. He is afraid someone has pilfered it from him.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes, and I heard a few of his neighbors on the same such-and-such street are complaining of the same condition. I would appreciate if you could look into this for they are all very upset.”

“And what is your relation to them?”

“They are cousins to me.” Tchitchikov thought. “Cousins-in-law. We are related by marriage.”

“All of you?”

“Yes,” Tchitchikov said.

“Oh,” the reporter said. “And what is your name again?”

Tchitchikov hung up. He glanced at the frontdeskman, who had taken to sitting down in a worn chair and was fanning himself. “A moment more,” Tchitchikov told him. He dialed again.

“St. Augustine Recorder, how may I help you?”

“Hello, my dear compatriot,” Tchitchikov thumbed through his notebook, “one Ms. E— W— has recently told me that the polling station found her vote cast before she had ever cut a chad.”

“We don’t have chads anymore.”

“Well, yes, but you know what I am saying?”

The woman on the other line thought. “No.”

“She has had a vote cast for her that she did not cast herself. Could you please investigate? Her address is…”

Tchitchikov relayed the message and smiled back to the frontdeskman. He was authentically engrossed in picking at something stuck between his teeth. “One more,” Tchitchikov told him, though he made no recognition of the utterance.

“Hello,” Tchitchikov said. “Is this DeWolf News Jacksonville?”

“Yes, what can I—?”

“The immigrants are voting! ELECTION FRAUD!!”

“Who, where, how?”

“All of them! Just—just all of them!”

“We’re on it!” The man hung up.

Tchitchikov replaced the earpiece and smiled congenially. “I’ll be back in an hour. Thank you,” he told the frontdeskman.

He left the motel. Now the cast die had no chance but to turn up a foul side.

****

Tchitchikov took the bus to Fairwell’s office to wrap up a few more loosened ends. But as he was walking toward the door, he was accosted by a familiar voice.

“Hey, Paul,” Aris said.

Tchitchikov was stunned; he turned to face the familiar, young copy of himself, but with less care to his morning toiletry and hair than usual. Tchitchikov was sad at Aris’ betrayal, and yet still thankful it was not his own. “What are you doing here?”

“I’m really sorry. I’m a piece of crap. Could you tell Jenna that? She’s not returning my texts.”

Tchitchikov felt the cold pang of sympathy. “I have a question, though. Why did you do it?”

Aris shook his head. “Achilles isn’t doing too well. Kingston approached me a while back. I couldn’t afford his surgery, it’s crazy, but…” Aris sighed. “I’m sorry.”

“I am as well.”

“He’s scheduled Monday next week. I hope the little bastard can hold out until then.”

“Me too,” Tchitchikov said. He nodded. “I will tell her that. I will relay your penance.”

“Okay, thank you,” Aris said. “Good luck.”

“You as well.”

He entered the office, busier than this weekend, though still halved in peoples, by the measure of the previous week. There was an eerie reserve of calm. Tchitchikov inquired about Jenna.

“Oh, she’s out and about at the polls, holding our signs,” O— said. “Hopping about. I’m not sure where. Sorry.”

“I see. And Selifan, is he in?”

O— shook her head. “He’s driving today.”

“Yes, he is always driving.”

“He’s dropping off people to polling locations,” she said.

“Oh. That makes sense.” Tchitchikov frowned. “I shall send a text message his way.”

As Tchitchikov typed on the sad cell phone, Andy approached him. “So that’s where my phone went.”

“Your phone?” Tchitchikov replied.

“Yeah. Fluffy and Cloudy are my favorite Magical Pegasi. Are you looking for Jenna?”

Tchitchikov nodded.

“She’s out holding signs. I’m holding down the fort. Something I can help you with?”

Tchitchikov mulled over a few things to say. He landed upon this: “No, just to thank you for the stay.”

“Sure! You’re welcome, Paul.” Andy smiled. “Are you leaving this time? I see you have your stuff.”

Tchitchikov nodded. “Soon.”

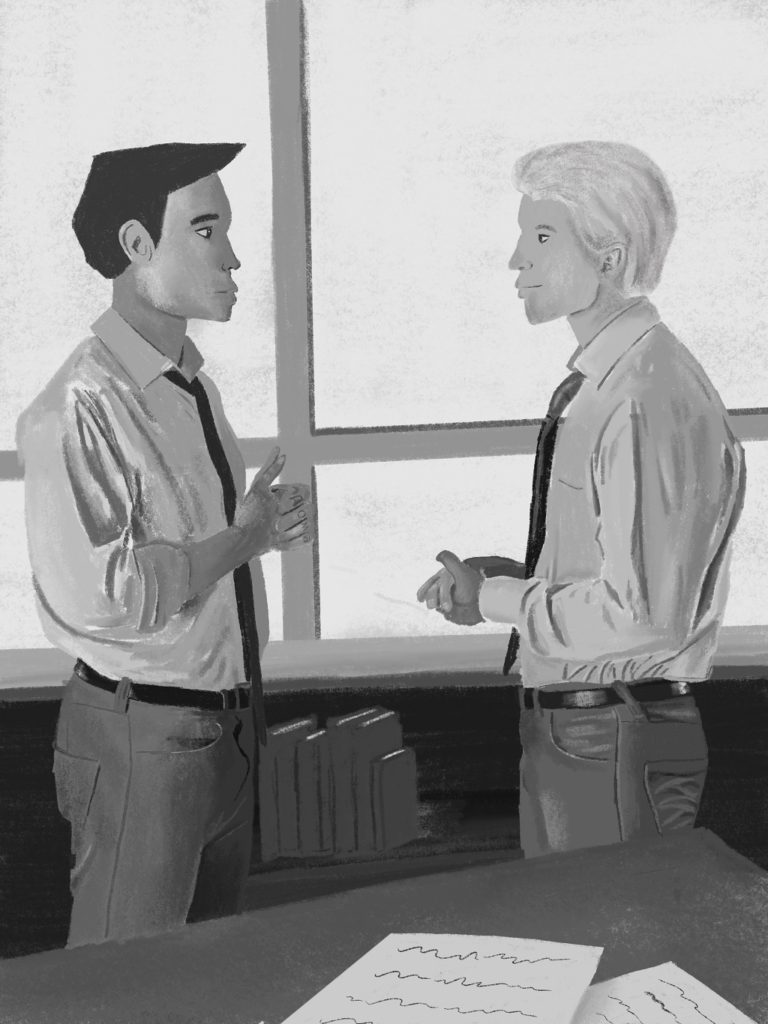

“Oh. Okay. It was a pleasure, my man.” He offered a shake, which Tchitchikov greedily took.

“I have a few things I need to do today,” Tchitchikov said. “Where is Jenna holding signs? I have a message to relay to her.”

Andy texted her and gave him the polling place and directions to it. Tchitchikov followed those directions and caught her on a median with another woman, both of them shouting and shaking signs, Fairwell: Fair Man for Congress. “Don’t forget to vote,” Jenna yelled at the traffic.

“Jenna, good morning,” Tchitchikov said.

“It’s afternoon, but hello all the same,” she said. “You come to help? We could use the visibility.”

“No,” Tchitchikov said. “Not today. I wanted to say something about Aris—” Jenna scoffed “—that you should consider his repentance and to forgive him.”

“Nope,” she said. “And if you can tell him to stop texting me, that would be fabulous.”

“Jenna,” he said, “do know that there aren’t many opportunities to offer forgiveness, and they should all be considered. And there are fewer opportunities to offer that same forgiveness to someone deserving of it.”

“Well, he should piss off. That’s what he deserves.”

“Do open yourself to the possibility of forgiveness,” Tchitchikov said. “That is all I am asking.”

Jenna’s eyes became slits. She sighed, a release came upon her, and she said, “Okay. I’ll consider. But only because you’re asking. That’s it. No promises.”

“That is all I ask.”

“Okay.” Jenna turned back to the traffic. “Are you leaving?”

“Yes,” Tchitchikov said. “Sometime today.”

“Okay.”

“Good luck today,” Tchitchikov said.

He crossed the street again, received a few honks from a driver or two, and waited by the polling station, a school along the route of the bus. He heard the many colors of invective from a man old enough to know many curse words, but seemingly too old to invoke them. He shouted one of the less creative ones and growled, turning to Tchitchikov.

“Can you believe it?” The man spat on the ground. “They said I already voted!”

“Did they?”

“I HATE WHITTAKER. There is no way on God’s dying earth I’d vote for his party. What is going on?”

Tchitchikov shook his head to help suppress a smile. “I do not know, but I suggest you might bring this to the attention of the local news.”

“You know,” the old man wagged his finger, “that’s a good point.”

“Is it not?”

“For a fellow with a weird accent, you’re talking sense.” The old man pulled out a flip phone. “Could you look up the newspaper’s number for me?”

“It so happens that I have it right here,” Tchitchikov said.

****

It took Tchitchikov one bus transfer and his last remaining loose papers to compose and write his letter:

Dear James Kingston,

You have beaten me. That is fine. And while you are finished with me, I am not finished with you. Not quite.

There is one last thing that needs to be said, and should I say it correctly, its effect shall haunt you that no blade shall cut it away, nor political suppression suffocate it:

You are a tool in a machine greater than yourself, one that feasts upon the souls of the living. The machine always hungers and it always feasts, and you shall find that out for yourself when there is no one left to help you. Names matter to tongues, not to teeth. May this truth haunt you.

Sincerely, your foe,

Tchitchikov

He was satisfied with the final product. Tchitchikov relaxed on the bus when a man more advanced in years than he stared at him for more than a few moments from the seat across. “Are you Greek?” he asked.

“No,” Tchitchikov said. “I am from St. Petersburg in Russia.”

He pointed to the letter. “Oh. So that’s not Greek there?”

Tchitchikov looked at the letter again. He had written it in his native tongue, in Cyrillic characters. “Oh blast.”

“So that’s Russian? Heck, it all looks Greek to me.”

Tchitchikov deflated. He rapped his fingers on the suitcase which served as his temporary desk. He stuffed the paper into it again.

“You don’t happen to have a piece of paper on you?” Tchitchikov asked.

“I’d love to see Greece someday. It sounds fantastic.”

Tchitchikov sighed. A few hours later, he arrived at the Rooster and the Dragon. Diner smells entered from the left half into the right half, where Tchitchikov took a seat.

“Hey there, Pavel,” Georgina said. “What can I do for you?”

“I have something I would like you to tattoo for me.”

“Huh.” Georgina pursed her lips. “I didn’t think you were the type for tattoos.”

“I am not, but it feels important at the moment. It is something I want to remember.”

“Okay.” Georgina leaned on a small table. “I advise people to wait on it a day. Impulse tattoos aren’t particularly fun for anyone.”

“Yes, but I suspect I might not have a day to wait.”

“Why’s that?”

“I might have demolished some suspension bridges.”

“Not sure what you mean, but demolition sounds fun,” she said. “What is it, then? A wolf? Lenin?”

“None of those. Just a phrase, ‘a soul at home.’” Tchitchikov nodded. “That is what I would like.”

Georgina hummed to herself. “Yes. I like that. I would actually advise getting that tattoo right away. It sounds lovely. Where would you like it?”

Tchitchikov brandished his pointer finger and pointed it to exactly no specific direction. “I am not sure, actually.”

Georgina took out her sketch pad began to pencil in it. “How about you figure out where you want to place this? One second.” She licked her lip and after a few moments flipped her sketch toward Tchitchikov, the phrase housed by an outline of walls and a pointed roof. “How about this?”

Tchitchikov squinted. “That is not how to spell it.”

Georgina flushed with alarm. She looked over her sketch and traced the letters with her finger. “I must be losing my mind. It looks fine to me. Wait, could you just double check my spelling?”

She offered the pad to Tchitchikov, who quickly wrote in it. “This,” he said.

She took a glance at it. “Aiwah what? Wait, is this Russian?”

Tchitchikov tipped the pad back in his direction and squinted at it. “Oh. Yes it is, apparently. I must be slipping into Russian again. What you have is fine.”

“No, wait.” Georgina got a ball point pen. “That’s perfect. Idea: come here.”

Tchitchikov approached Georgina’s desk and she laid his hands on it, palms down. She sketched the letters on his knuckles. “That looks pretty badass,” she said. “What do you think?”

“I think you don’t know what a de looks like. Hold on.” Tchitchikov sketched out the Cyrillic characters more carefully and Georgina nodded. “There,” he said.

“Okay, go clean off,” she said. “Use the hand sanitizer over there. I got you.”

****

It was more painful than Tchitchikov anticipated.

But, as some might say, “No pain, no gain.” Others might say, “Pain in love,” and sometimes a work of art is one of pain and love. I can confirm this notion. “Let’s see it,” Georgina said.

Tchitchikov had some trouble making fists, as his fingers were stiff, yet he suffered through it (he has suffered through much so far, so what is a little more?) and produced his tattoo to her. “Do I punch someone with this?”

“Hold on, like this.” Georgina gently touched Tchitchikov’s raised fists and carefully touched them together. “That’s what you’re supposed to do. That’s how you show it to people.”

“Like I am hanging onto a ledge?”

“Well, yes, I suppose.” Georgina scratched her head. “Imagine you’re holding onto a pipe or something. A bag. I don’t know.”

“The rollercoaster of life?”

Georgina laughed. “I’ll take it. Is it okay?”

Tchitchikov turned the two fists toward himself. “Yes. It is actually quite splendid.”

“Good,” Georgina said. “That’s the only one of those I’m going to do. I promise.”

“Could I borrow your pad? I have a letter I need to rewrite.”

Georgina offered it and the pencil to him, except Tchitchikov was unable to handle the pencil without extreme pain. He dropped it, picked it up, and dropped it again. “Could you write something for me?”

“Sure. What is it?”

Tchitchikov laboriously opened his suitcase and produced the letter he wrote in Russian. “A curse and a prophecy I want to send. The letter I want to write is thus: Dear James Kingston—”

“Is that in Russian, too?”

“It is, hence why I need it Americanized.”

“Huh.” Gerogina said, “Why don’t you just send it like that?”

“Then he cannot read it.”

“It may be my working in Cyrillic, but I think a Russian curse is more powerful than an American one.”

Tchitchikov thought. “Well, we do have much more experience in such things as suffering and curses.”

“Cool. Glad I could convince you.”

“Do you have a postal stamp for it?”

“Do I look like I can afford my email?” Georgina asked. “How do you think I can afford real mail? “

“Oh, well…”

“Just kidding. I definitely don’t have any. But don’t worry, I’ll find one for you.”

“Thank you.”

Georgina shook her head. “You Russians are too serious. I’ll get it mailed.” She looked at her phone. “You’re coming tonight, right?”

“Tonight to what?”

“Tonight to Fairwell’s victory party. Selifan will be by in an hour to pick us up. He’s finishing up driving. The polls are gonna close soon.”

Tchitchikov had not received word back from Selifan. “Then, yes,” he said. For I shall need him one last time, he thought to himself.

****

Georgina, Selifan, and Tchitchikov arrived at Fairwell’s office. Georgina waited for the two to leave the car.

“One moment, darling,” Selifan told her. “We shall catch up.”

She nodded, and Selifan turned to Tchitchikov. “Tonight?”

“Yes,” Tchitchikov said.

“I saw your tattoo. Why that?”

“A reminder.”

“Of what?”

“Of some sense of home.”

“It is nice to be settled,” Selifan said.

The two gave a few moments into the heavy air. The air held those brief moments, but Selifan and Tchitchikov knew there was far many more to come this night, and they left the car to march toward them.

The office was packed more than in the morning. It was bustling with youth and noise and humidity and food smells. A local news station eked out a small vantage from which to view the office, though the reporter and camera-woman were chatting and sipping from bottles of water. A few televisions were planted on desks in the room. Fairwell was not in the crowd.

Tchitchikov directed his attention toward one of the televisions to another local station interviewing an older woman, who was in the heated throes of verbal exchange. Despite the noise in the office, Tchitchikov made out a few of her verbal exchanges:

“…don’t understand why … the Russians? Did they steal my … ? I don’t get it. In all my … I’ve never seen … My vote! Where’s my vote?”

The reporter on the television nodded and mmm-hmmed and offered nothing more to the distraught older woman. Were Tchitchikov there in person, he could have at least offered her a wry snicker, which he instead gave away in Fairwell’s office to no one in particular save himself.

“Turn it up, they’re reporting results!”

The office hushed. A few of the younger crowd bent into their laptops, and the televisions were indeed turned up in volume. A woman stood in front of a map of the Congressional districts of Florida, and the news ticker at the bottom kept the audience informed by and captivated with a procession of numbers and percentages.

“…this highly contested year. We have the first figures coming in from Duvall county, and even though it looks neck-and-neck, keep in mind less than five percent are reporting. We’re going to turn to our analysts to ask them what to expect tonight.

The camera switched to a round desk with four political analysts: a white man in a suit, a black man in a suit, a white woman in a red professional-looking dress, and a tanned woman, Tchitchikov couldn’t make out her ethnicity, but made out a pin of a flower on the lapel of her gray suit jacket. The white main in the suit led them off.

“This year,” he said, “we have the most contested midterms in the state in almost twelve years. There are a total of five seats on the House being challenged, and one in the Senate, Senator Whittaker, of such-and-such Party who faces a tough race against a liberal insurgent. What should we expect? I think this year is a moratorium on whether Floridians feel that their Congress is doing a good job. There are clearly those who feel they could do better, but ultimately, it’s the voters who have to decide that question: can the challengers do a better job?”

“Yes,” the black man said, “I agree: the voters will decide who can do a better job. Will it be these new faces, young upstarts in Alachua, Sumter and Duvall Counties? Will more traditional opponents prevail in Palm Beach or Nassau? Or will the voters decide that, yes, they trust the direction their Congress has taken, and that everything is on a safe, stable path?”

The white woman spoke up. “Yes, we shall see this moratorium, as you so gracefully put it, addressed and answered tonight. Will Florida want a new direction? That’s the question for tonight.”

The woman in the gray jacket blinked blankly a few times. “Yes. Voters are going to decide tonight.”

Fairwell weaved through the seated volunteers, shaking hands and smiling appropriately. He took a seat in roughly the middle, and one of the volunteers patted on his shoulder extra luck. Tchitchikov saw a woman in the back, against the wall, an appropriate age to be his wife.

Tchitchikov turned to the television again, watching the woman at the county map. “Duvall County is off to a competitive start, again, five percent of precincts reporting, with Fairwell’s and Kingston’s race a really heated contest here. I believe we should weigh in on these two.”

The black man spoke. “Here we have Fairwell, a relatively unknown incumbent, in what’s certainly an unusual kind of race: polls have shown Kingston to have the greater name recognition. Which is no small factor, especially given that Representative Fairwell recently has come under fire for what has turned out to be a big scandal, his infidelity to his wife about five years ago.”

“Yes,” the woman in a dress said, “I personally find it disgusting that he betrayed his wife, and I feel that the voters could well punish him for his lack of moral courage.”

The woman in the grey jacket said, “I find it rather convenient that Fairwell’s affair may be the story of this race, considering that Kingston himself has had quite a rap sheet for an aspiring representative.”

The other woman jumped in. “Yes, but this is—”

“Hold on, I wasn’t finished.” the woman in the jacket continued. “The disgusting part of this story is the massive media coverage of Fairwell’s affair. This network dedicated almost twenty-eight hours to this scandal in the past five days, since the story broke Friday. Do you know how much airtime Kingston’s DUI and accident received on this same network?”

“Well now,” the white man spoke up, “I don’t believe that’s entirely accurate—”

“Less than an hour and a half, and it hasn’t been mentioned since August, even though the civil proceedings are still under way. Two segments total; yes, I counted. Doesn’t that tell you something about the media’s priorities, specifically this station’s priorities?”

The other three analysts were silent.

Tchitchikov turned to a young man on his laptop. “Western Jacksonville is looking pretty good,” he said, his face buried in it. “Fifty-seven, forty-one.”

There were murmurs of hope.

“…Taber did the tried-and-true approach,” the white analyst said. “Immigration is a huge factor, and you can’t discount it. If he keeps his seat tonight, that was the reason he did. Or one of the biggest reasons.”

“Again, I agree,” said the black analyst, “but do keep in mind, we’re not quite at twenty percent reporting. He hasn’t won yet. I suspect Taber will keep his seat as well, and yes, immigration is one of the biggest issues of this midterm.”

“I agree,” the woman in the dress said. “Their tough-on-immigration stance is what Taber and Martinez have hammered home all through their campaigns. And voters seemed to have responded! Now Everly’s staunchly pro-business platform—I’m sorry, where is he at?”

The camera shifted to the woman at the map. The map was starting to gain color. “Right now, ninety to less than ten percent, with thirty-five percent of precincts reporting.”

“Yes,” the woman continued, “the economy is another big issue on the minds of voters. Everly’s political ads hit this issue again and again. Is it safe to say Everly has successfully defended his seat yet? I think we know why he kept it this year.”

The woman in the jacket spoke up. “Well, yes, immigration and the economy have perennially been the two major issues in Florida politics for the past twenty years. You’re going to find that with most of the country, even in conservative Midwestern states like Minnesota. We can take that for granted. Now, what I think is the real story here is the emergence of a third major issue last election and now at the forefront of this election: the issue of major discontent. Yes, the economy is doing well, but people aren’t. The working class are hurting. They’ve seen stagnant wages since—”

The black man interjected. “I don’t see what you’re saying. The economy is doing well, people are doing well—”

“I didn’t finish,” the woman said. “Since the eighties, yes, the eighties, minimum wage, and real wages, has hardly done up, while worker productivity has skyrocketed. There’s a disconnect: the economy is not the working class. The economy, specifically the stock market, the Dow Jones, all those little tickers at the bottom of the screen have nothing to do with the average Floridian who’s living on a seven-hundred dollar Social Security check every month.”

“Seven hundred?” The woman in the dress scoffed. “I don’t buy it. Where do you get your…?”

“Eastern Jacksonville coming in,” the young man at the laptop said.

“What’s it look like?” A young woman asked him.

He frowned. “Kingston so far. But we kind of knew this, as long as we can scrape by in the other precincts.”

“We’re at almost fifty percent reporting,” the woman at the map said, now filling in with color, “and it’s clear Representative Everly has maintained his seat, we called it a few moments ago. But if you look at Duvall County, Fairwell is actually behind, forty-seven percent to about fifty-one. What do you make of this?”

The young man at the laptop frowned harder. As the results came in, the discussion on the television grew more heated.

“I’m not saying Everly did commit fraud,” the woman in the jacket said. “We’d need evidence for that. But I am saying that something is fishy in this election. I’ve seen almost half a dozen stories of people whose votes seemed to have been cast well before they hit the polls.”

“Oh please,” the woman in the dress shook her head. “Of all the things I’ve heard, this is not the story of tonight’s election. Was that garbage on your blogs?”

“You shoudn’t discount how serious this is!” The woman in the jacket sighed. “And yes, I do keep open to media other than cable news, and this is a story that I think is going to break soon. Now whether mainstream media is smart enough to pick up on it and report it…”

The numbers flowed in. At sixty three percent in Duvall County, the young man reported forty-three to fifty-two, Fairwell trailing. The crowd of young people started thinning.

“We still have a chance,” the young man said.

“I feel that we’re going to see a vindication for almost all of these races,” the black analyst said. “We have Everly and Taber clearly with the voters’ mandate, and it’s looking like Julio Martinez is going to hold onto his seat as well.”

“That may be for this election,” the woman in the gray suit said, “but it’s foolish to discount the real pain the voters are going through. Poverty levels in the state are almost fourteen percent. But actual poverty—can a person put food on the table, keep a roof over her head, even retire?—those levels are not accurately reported. Let me say, the Federal Poverty Level guideline for a single adult is around twelve thousand; now, tell me how much you have to make to afford an average apartment in the state at a thousand dollars per month. Would you have to make twenty-four thousand to scrape by? Twenty-thousand certainly doesn’t cut it. That twelve thousand is a cruel joke.”

The figures were forty-one to fifty-three at seventy percent reporting. The young man shook his head and the crowd thinned. “He can still get this,” someone in the back said.

“The voters want someone with new ideas,” the white analyst said. “It looks like they chose James Kingston, so far, over Fairwell, because of Kingston’s progressive messaging.”

“I’m not sure what’s progressive about James Kingston,” the woman in the jacket said. “He espouses the same policies that are so rampant in his, let’s face it, insular and even racist party.”

“Racist?” The white man said.

“When you demand IDs to vote, which impacts voters of color so disproportionately—and this is true, voters of color have less access to driver’s licenses and other forms of government ID—then you suppress the votes of minorities. If anything decides this election, it’s the massive voter suppression—”

“What voter suppression?” The black man asked. “What are you talking about?”

“These policies don’t need to be overtly racist. They don’t need to say ‘separate but equal.’ But they do target voters of color, whom, we’ve seen in polls, tend toward more progressive policies like raising the minimum wage, healthcare for all—”

The woman in the dress rolled her eyes. “I wish you’d go away…”

The crowd was thin. Jenna moved to an empty seat by Fairwell. The young man closed his laptop and stared down.

“We’re now declaring a massive upset, with James Kingston winning Duvall County’s seat in the House from Alexander Fairwell, fifty-six percent to forty, with eighty-two percent of precincts reporting.” The woman at the map nodded toward the table of analysts.

“Well I’m not surprised,” said the white analyst. “Fairwell was out-performed, and the scandal caught up with him.”

“Yes,” the woman in the dress said. “That horrible scandal.”

The black man nodded. “It’s clear that the wrong message, and that scandal, made voters choose a new, fresh voice. It was Kingston’s seat to win. Now what was interesting tonight was Alfred Stoddard’s victory, after a rather huge upheaval in his campaign—”

The television was turned off. Jenna turned to Fairwell. “There’s still eighteen percent left to count. What if…?”

But Fairwell didn’t hear her. He nodded solemnly, and something slipped off of his mind. He smiled. His wife came from her position on the wall and rubbed his shoulders from behind.

“I’m so sorry,” she said.

He placed his hands on hers and rubbed them. Fairwell chuckled and shook his head to himself.

“It’s still … you still might…” Jenna said.

Fairwell stood up and kissed his wife on her lips. He pulled back and petted her cheek.

“There’s still a chance, right?” Jenna asked him.

Fairwell smiled to her. He took his wife’s hand, and they left the mostly-empty office—the reporter was packing up—with an impenetrable cloud of silence and understanding. Jenna, Andy, Tchitchikov and Selifan remained, and Jenna, after several more moments, would lock it up.

****

It was a late ride to the bus station.

“I am sorry we have missed the train,” Selifan told Tchitchikov.

“Well I am not,” Tchitchikov replied. “It is important to see things to the end.”

“And this is the end.”

“Yes,” Tchitchikov said.

Tchitchikov glided his hand on the air currents as the Jacksonville night passed him by.

“It was a lovely run,” he said.

Selifan smiled. “Yes. It was.”

Would you not agree my reader? Was this adventure not a lovely one, though ending on an unexpected note?

We are never guaranteed a victory, though we fight for it, and may not even make a blunder at it. Sometimes the odds are too stacked against. Sometimes it is too high a mountain to climb. I would like to think Tchitchikov learned this, and perhaps even Fairwell, to some extent. And of that failure, or rather, that miss at victory: what of it? What comes next? Do we pack up and go home, and give up as our defeated representative did?

That is an individual choice. Sometimes we need to heal. There is no shame in that; it is part of life and action and, yes, the Fight.

We may or may not come back to that Fight again, but realize, or at least hear my thoughts on this, that having been in the Fight, even for but a moment, that is what counts. Whether we complete it, in victory or defeat, as long as we have participated, that is our good deed to the world, that is our Dostoevskian onion, the painful vegetable to carry us from hell’s grasp when our time should come. I would like to think that action, regardless of other inaction, is our salvation in the eyes of the after-life, whatever that may turn out to be.

And an onion at that moment texted Tchitchikov. I apologize, a metaphorical onion, not a literal one, but you shall see soon, my reader.

Tchitchikov frowned at the text.

“What is it?” Selifan asked.

“I realize it is nearly midnight,” Tchitchikov said, “and I do not know what may come of this, but I have one more visit to pay before my departure.”

****

Stoddard’s office was dimmed. Tchitchikov knocked, and Stoddard opened the door. “Welcome,” Stoddard said.

There were not many remnants of a party there, not that the remnants had been cleared away, but Tchitchikov had the sense that it was a small party for his victory. Stoddard waved at a chair, “Take a seat,” he said, and he sat on his desk. “I appreciate your coming so late,” Stoddard said.

“I am not sure of your insistence,” Tchitchikov said. “But yes, here I am. What is the matter, then?”

Stoddard frowned. “So, I’m not sure where to start.” He nodded a few times. “When you’re imprisoned a long time, it’s a strange place. You don’t hate it. It’s what you know.”

“I see,” Tchitchikov said.

“It’s something you get used to. In a way. There’s a certain, I suppose, stifling notion to the air. It gets thick and tough to breathe. And after time, it only gets thicker and thicker, but you’ve been breathing it for so long, it’s easier to keep at it, even knowing that one day it will choke you.” Stoddard knit his fingers together. He stared down, and willed them out of their nervousness, loosening them and placing them on his thighs. “It’s hard. Sometimes you can’t escape. Sometimes it’s impossible.”

“I would assume escape would be exceedingly difficult,” Tchitchikov said.

“I’m not sure you understand me,” Stoddard said. “My whole life, I’ve been imprisoned. That day you came by, you loosened my shackle—Stu—and for some reason, I felt I could—and should—undo it. He is gone. And I was terrified. That’s the worst part of losing your prison, the absolute, abject terror. The fear that you will plummet endlessly. And I did.” Stoddard smiled. “Until I didn’t.”

Tchitchikov tried to gauge him. “Freedom,” he said.

“I realize this now, what makes one man different from another. We all have our prisons, our sufferings. Some walk away and say, ‘never again, never again will I suffer.’ It is selfish, but I understand it. And some say, ‘never again, not to another soul.’ I have suffered and survived, and I know I will survive should it happen again; but I also know these things must never happen to another.” Stoddard nodded nervously. “You have powerful enemies.”

“I do have powerful enemies,” Tchitchikov said.

“Then it is settled.”

“What is settled?”

Stoddard stood up. “There is much for us to do, dear friend.” Stoddard presented a handshake. “Come, join me. In this last term of mine, I intend to do some good.”

Tchitchikov stared at Stoddard’s hand for a few incredulous moments before he realized this was the destiny he had always craved.